When you're navigating the complexities of ADHD—whether for yourself, a loved one, or to better understand its place in the world—it’s easy to feel lost in a sea of changing definitions, historical misconceptions, and seemingly conflicting perspectives. The medical journey of ADHD, intertwined with the powerful rise of the neurodiversity movement, presents a rich, often challenging, but ultimately empowering story. Understanding this history isn't just an academic exercise; it's a vital step in evaluating current approaches, reducing stigma, and confidently moving towards a future that embraces neurological differences.

We’re not just looking at dates and diagnoses; we’re exploring how society's lens has sharpened and shifted, transforming "moral failings" into recognized neurological patterns, and "disorders" into diverse ways of being. This deep dive will provide you with the contextual clarity you need to discern authentic, supportive resources from outdated narratives.

The History of ADHD & Neurodiversity: From Pathology to Pride

The journey of understanding ADHD is really a tale of two narratives: the evolving medical classification that sought to define and treat symptoms, and the burgeoning neurodiversity movement that champions acceptance and celebrates neurological variances. These stories, once disparate, are now converging, offering a powerful framework to appreciate the full spectrum of the ADHD experience.

The Shifting Lens: How We Came to Understand ADHD

For centuries, behaviors now recognized as ADHD symptoms were often misunderstood and pathologized, leading to immense personal and societal challenges. The path to our current understanding has been anything but linear; it's a winding road paved with groundbreaking research, shifts in societal values, and the tireless advocacy of countless individuals.

Part 1: The Medicalization of "Difference" - History of ADHD Diagnosis

The formal journey of ADHD as a medical concept began with early observations of children exhibiting what we now understand as attention and hyperactivity challenges. It wasn’t a sudden discovery but a gradual crystallization of symptoms into recognized conditions.

Early Observations: The Seeds of Inattention (Late 1700s - Early 1900s)

Long before ADHD was a known term, astute observers noted patterns of behavior that would eventually form its diagnostic bedrock.

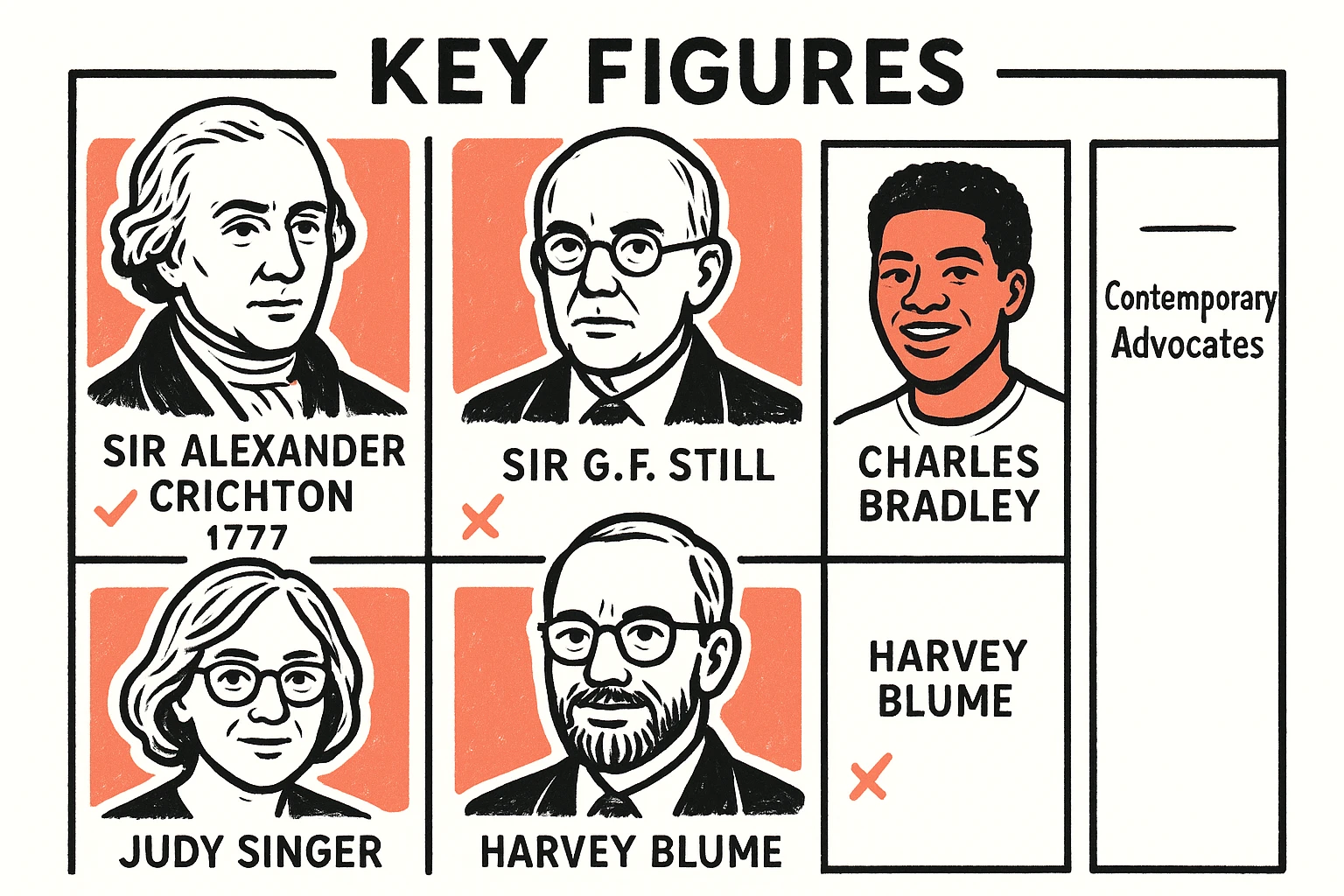

- In 1775, Melchior Adam Weikard described “attention deficits” in adults, noting a lack of sustained focus. Just over two decades later, in 1798, Scottish physician Sir Alexander Crichton wrote of "mental restlessness" and the inability to "attend with constancy to any one object." These early descriptions laid the foundational understanding that difficulties with attention were not merely moral failings but intrinsic cognitive challenges.

- The early 20th century marked a significant turning point. In 1902, Sir George Frederic Still, a British pediatrician, delivered a series of lectures describing a group of children with "an abnormal defect of moral control." These children, despite normal intelligence, exhibited significant problems with sustained attention, impulsivity, and hyperactivity, seemingly oblivious to consequences. Still's work is widely considered a foundational clinical description of what would later become ADHD. He noted these issues weren't due to poor upbringing but rather an organic, biological basis.

This period saw the introduction of terms like "hyperkinetic disease," reflecting an initial focus on the visible hyperactivity element.

The Dawn of Diagnosis: DSM Eras (Mid-1900s onwards)

The official recognition and categorization of ADHD-like symptoms within diagnostic manuals truly began to shape its clinical trajectory. The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM)—the authoritative guide published by the American Psychiatric Association—has been central to this evolution.

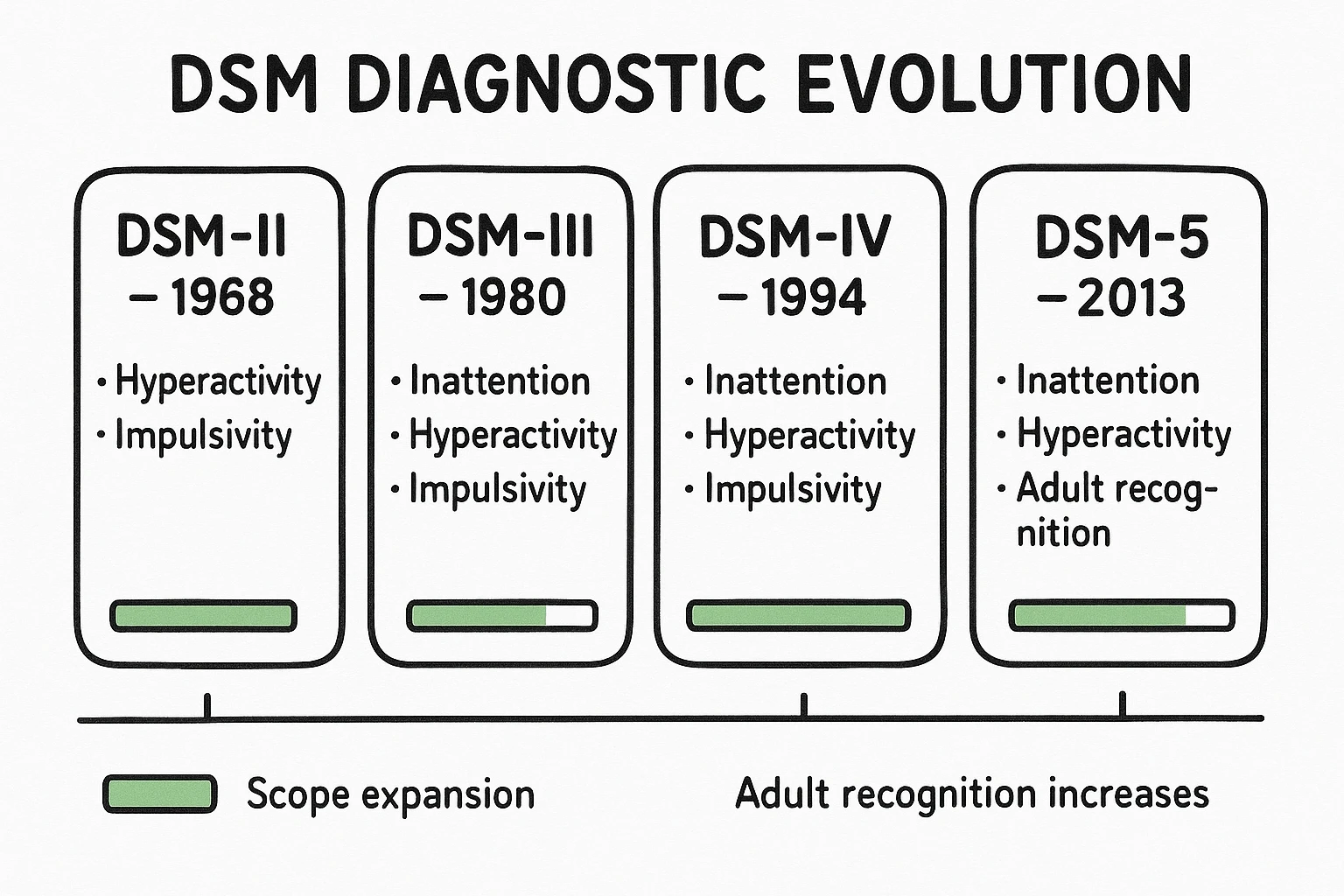

DSM-II (1968): Hyperkinetic Reaction of Childhood

This was the first official classification, primarily focusing on hyperactivity. Children were described as "overactive, restless, distractible, and having a short attention span." The emphasis was largely on the disruptive external behaviors, with less attention paid to the internal experience of inattention.

DSM-III (1980): Attention Deficit Disorder (ADD) with or without Hyperactivity

A pivotal moment arrived with DSM-III. For the first time, inattention was explicitly recognized as a core component, not just hyperactivity. This led to the creation of two subtypes: ADD with hyperactivity and ADD without hyperactivity. This was a crucial step in acknowledging that many individuals struggled with attention even if they weren't overtly hyperactive. The introduction of clearer diagnostic criteria in the DSM-III also contributed to a significant increase in ADHD diagnoses in the 1990s, especially after the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990 provided legal protections.

DSM-III-R (1987): Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) Unified

Just seven years later, the DSM-III-R consolidated the two ADD subtypes into a unified diagnosis: Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD), recognizing that both inattention and hyperactivity/impulsivity could coexist or present differently. While the "ADD" moniker without hyperactivity persisted in common parlance, clinicians were now primarily using ADHD.

DSM-IV/IV-TR (1994/2000): Subtypes Emerge

The DSM-IV further refined the diagnostic criteria, introducing three distinct "presenting types" or "subtypes":

- Predominantly Inattentive Presentation (ADHD-PI)

- Predominantly Hyperactive-Impulsive Presentation (ADHD-HI)

- Combined Presentation (ADHD-C)

This distinction acknowledged the varied ways ADHD could manifest. Crucially, the DSM-IV also formalized the recognition of ADHD in adults, marking a significant step beyond the historical focus on childhood.

DSM-5 (2013): Presentations and Lifespan Recognition

The most recent iteration, DSM-5, brought refined criteria and changed the classification from "subtypes" to "presentations." It also adapted the criteria to better fit adult manifestations, recognizing that symptoms might present differently with age. The onset age for symptoms was pushed from before 7 to before 12 years, making it easier for adults who were not diagnosed as young children to receive a diagnosis. This revision affirmed ADHD as a neurodevelopmental disorder that persists across the lifespan.

Key Figures in ADHD Research

Beyond Crichton and Still, other pioneers shaped our understanding and treatment of ADHD:

- Charles Bradley: In 1937, Bradley accidentally discovered that stimulants could dramatically alleviate hyperactive behaviors in children, leading to the first effective pharmacological treatments.

- Stella Chess: Her work in the 1960s contributed to the understanding of temperament and how certain traits associated with ADHD were not simply behavioral choices.

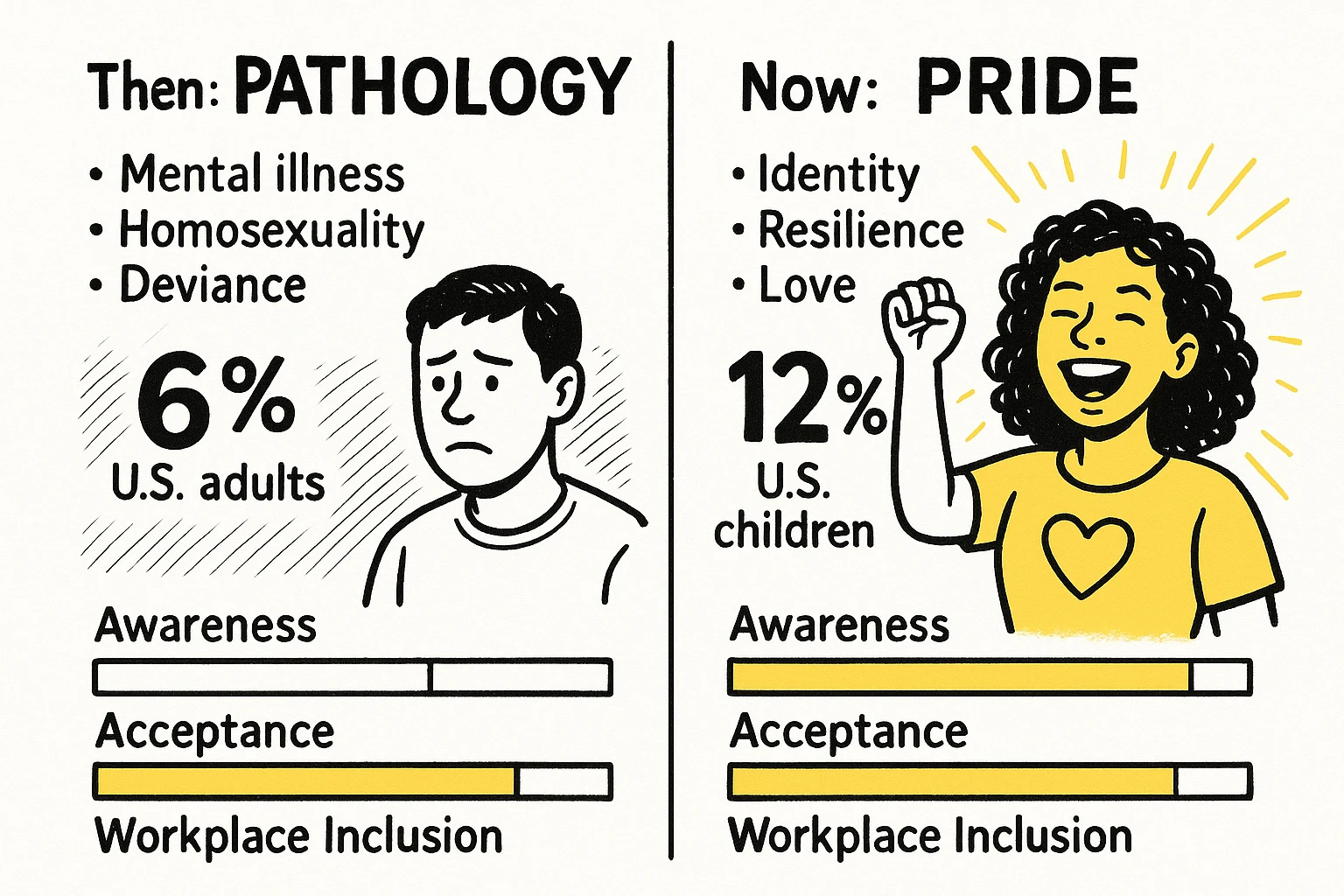

The Numbers Game: Prevalence Over Time

The evolution of diagnostic criteria, coupled with increased public awareness, has corresponded with a notable rise in diagnoses. By the mid-2000s, ADHD became a commonly diagnosed condition. Current estimates suggest that approximately 6% of U.S. adults and 8.7% of adolescents are diagnosed with ADHD. A 2023 CDC estimate found that 12.0% of children (aged 3-17) had received an ADHD diagnosis. These numbers, while showing broad prevalence, also reflect improved diagnostic accuracy and reduced stigma, suggesting that many individuals who might have been undiagnosed in previous eras are now receiving the support they need.

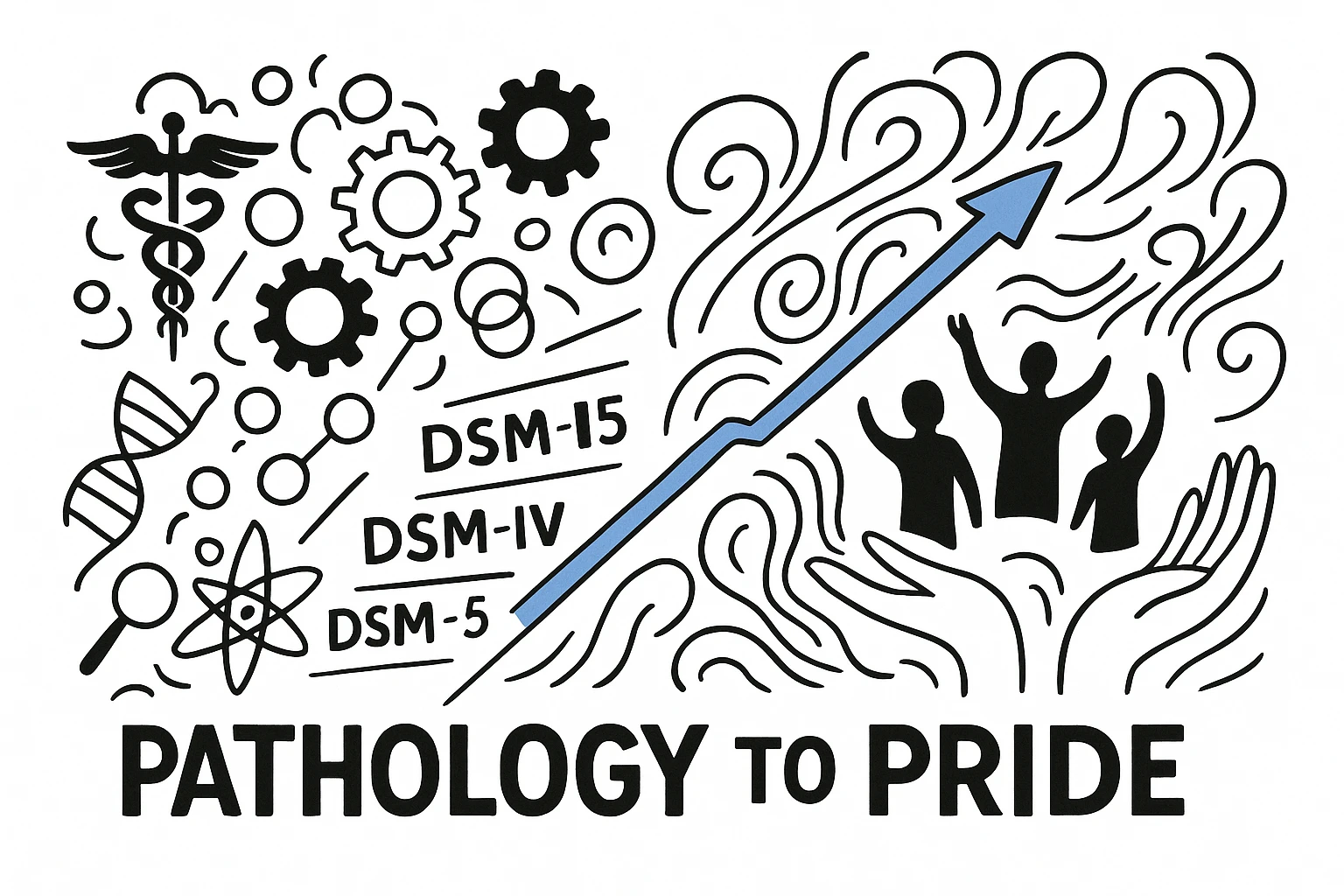

Image 1: A parallel timeline traces medical DSM milestones alongside the rise of the neurodiversity movement, highlighting when and why views of ADHD shifted.

Understanding the DSM Evolution: A Comparison

It’s helpful to see how much the understanding of ADHD has changed just within the major DSM revisions.

Image 2: A clear side-by-side comparison of DSM editions highlights how ADHD diagnostic criteria expanded and shifted across decades.

For more on how these shifts impact current diagnostic practices, explore "The Origins of ADHD Diagnosis."

Part 2: Beyond Pathology - The Rise of Neurodiversity

While the medical community was refining its understanding of ADHD, a parallel and ultimately revolutionary movement was gaining momentum: neurodiversity. This framework fundamentally challenges the medical model of disability, advocating for the idea that neurological differences, like ADHD, autism, or dyslexia, are simply natural human variations, not defects to be cured.

Roots in Advocacy: Disability Rights & Autism Movement

The neurodiversity movement didn't emerge in a vacuum. Its philosophical roots are deeply intertwined with the broader disability rights movement of the mid-to-late 20th century, which championed inclusion and challenged systemic ableism. Crucially, the autistic rights movement, spearheaded by autistic individuals themselves, was a key precursor. Groups like Autism Network International, founded in the 1990s, promoted self-advocacy and a positive autism identity, laying vital groundwork for the concept of neurodiversity. They argued for acceptance and accommodation over attempts to "normalize" autistic people.

The Coining of "Neurodiversity" (1990s)

The term "neurodiversity" itself was coined by Australian sociologist Judy Singer in 1998. Around the same time, American journalist Harvey Blume popularized the concept, writing that "Neurodiversity may be as important for the human race as biodiversity is for life in general." Singer envisioned neurodiversity as a human rights issue, a call for society to view neurological differences as valuable contributions to human experience, rather than deficits.

Neurodiversity & ADHD: A Growing Alliance

Within this new paradigm, ADHD finds a powerful reinterpretation. Instead of merely a collection of symptoms or a "disorder" to be managed, ADHD can be understood as a unique neurological operating system with its own pattern of strengths and challenges. The neurodiversity framework encourages:

- Strengths-based perspectives: Shifting focus from what ADHD individuals lack to the unique talents they possess, such as hyperfocus, creativity, innovative thinking, and high energy.

- Challenging stigma: Directly confronting the idea that ADHD is a "defect" or "failing," and instead promoting self-acceptance and pride.

- Neuroinclusion: Advocating for environments (workplaces, schools, social settings) that are designed to accommodate and leverage neurodivergent ways of thinking and being. This includes promoting practices like flexible work arrangements, sensory-friendly spaces, and communication adjustments.

Key Figures in Neurodiversity Thought

The movement is rich with influential voices. Beyond Singer and Blume, figures like Jim Sinclair (a foundational voice in autistic self-advocacy), and contemporary advocates who tirelessly work to educate, empower, and build inclusive communities, continue to drive the movement forward.

Image 3: Profiles of pioneers and advocates show who shaped both the medical narrative and the neurodiversity movement, aiding credibility assessment.

For a deeper look at these thought leaders, see our section on "Pioneers of Neurodiversity Thought" and further resources from Caltech and Institute4Learning.

Part 3: From Pathology to Pride - The Unified Narrative

The true power of understanding the history of ADHD and neurodiversity lies in seeing how these two seemingly different trajectories converge to create a more holistic and empowering view. We are moving from a past defined by deficits to a future embracing differences.

Deconstructing Stigma: Historical Misconceptions vs. Neurodivergent Reality

Misconceptions about ADHD have deep historical roots. For centuries, symptoms were wrongly attributed to "moral defects," "bad parenting," or simply "laziness." Even today, many struggle with the idea that ADHD is a "fad diagnosis" or "not real." This historical context helps us understand why these damaging myths persist.

- Then (Pathology): ADHD behaviors were viewed as willful disobedience, lack of self-control, or poor character.

- Now (Pride/Neurodiversity): ADHD is recognized as a neurodevelopmental difference with genetic and brain-based origins, encompassing a unique set of cognitive strengths often overlooked by traditional metrics.

The neurodiversity framework directly challenges this inherited stigma by reframing the conversation. It emphasizes that the challenges associated with ADHD often stem from a mismatch between neurodivergent individuals and environments designed for neurotypical brains, rather than inherent flaws.

Influential Voices & Future Directions

The movement for neurodivergent rights continues to grow, fueled by influential voices across scientific, advocacy, and corporate spheres. Emerging trends point towards a future marked by:

- Strengths-based approaches: Moving beyond deficit repair to actively cultivate and leverage neurodivergent talents in education and professional settings.

- Workplace neuroinclusion: Organizations are increasingly recognizing the vast untapped potential of neurodivergent employees, leading to the development of tailored hiring practices, accommodations, and support systems.

- Evidence-based neuroinclusion frameworks: A growing body of research supports the business case for neurodiversity, demonstrating its positive impact on innovation, problem-solving, and team performance.

If you're eager to learn about ADHD's presence throughout history, consider our "ADHD in Historical Figures" section, where we explore speculative examples like Albert Einstein and Leonardo da Vinci.

Conclusion: Embracing Neurodivergent Futures

The journey from viewing ADHD as a "moral defect" to celebrating it as an aspect of neurodivergent pride is a testament to scientific progress, human empathy, and relentless advocacy. By understanding its complex history, we can better appreciate the progress made, recognize the ingrained biases that still exist, and work towards a more inclusive future. This historical lens empowers individuals with ADHD to find self-acceptance and allows society to harness the unique contributions of all minds.

As you continue your evaluation of resources and approaches to ADHD, remember this unfolding history. It’s not just about understanding a condition; it’s about recognizing a diverse and valuable part of humanity. Ready to take the next step in empowering your own journey?

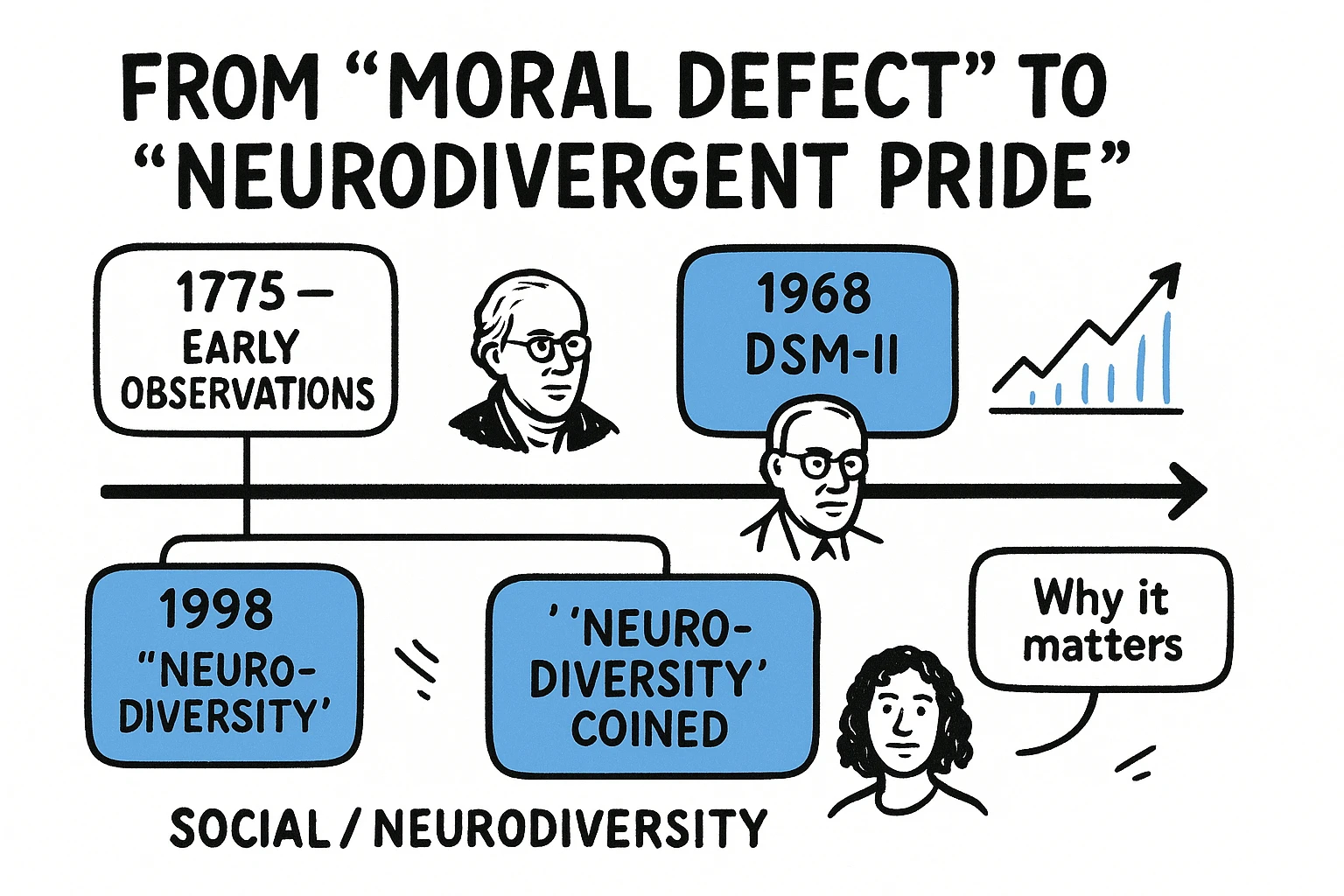

Image 4: A comparative panel reframes ADHD from stigmatizing history to strengths-based pride, using bold numbers and progress bars to show change and progress.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Q1: What was ADHD called before it was ADHD?

Early observations referred to symptoms as "mental restlessness" (Crichton, 1798) or "abnormal defect of moral control" (Still, 1902). In diagnostic manuals, it was first called "Hyperkinetic Reaction of Childhood" (DSM-II, 1968) and then "Attention Deficit Disorder (ADD)" (DSM-III, 1980).

Q2: When did neurodiversity become a widely recognized concept?

The term "neurodiversity" was coined by Judy Singer in 1998, emerging from the autistic rights movement of the 1990s. Its recognition has grown significantly in the 21st century, increasingly influencing how society views neurological differences.

Q3: Does the history of ADHD mean it's not a real condition?

Absolutely not. The historical evolution reflects a deepening scientific understanding, not a fabrication. Early observations in the 1700s and 1800s, confirmed by modern neuroscience, demonstrate that ADHD is a well-documented neurodevelopmental condition with biological and genetic underpinnings, not a social construct or a "fad diagnosis."

Q4: How did the DSM changes impact people with ADHD?

Each DSM revision brought significant changes. The DSM-III recognized inattention, helping those without overt hyperactivity get diagnosed. Later revisions (DSM-IV, DSM-5) acknowledged ADHD in adults and refined criteria, leading to more accurate diagnoses across the lifespan and a better understanding of diverse presentations. These changes helped many gain access to support and understanding, reducing the feeling of being misunderstood, which was a pre-purchase pain point for many.

Q5: How does the neurodiversity movement help destigmatize ADHD?

The neurodiversity movement reframes ADHD from a "disorder" to a natural human variation, akin to biodiversity. It emphasizes strengths, advocates for acceptance, and pushes for societal adaptations rather than solely focusing on "fixing" the individual. This approach helps battle the internalized stigma associated with ADHD as a "disorder" or "laziness" and contributes to a sense of belonging. The movement encourages seeking validation for personal experiences.

Q6: Are there common misconceptions about ADHD that historical context helps to address?

Yes, many. Historically, ADHD symptoms were oftenmistakenly attributed to "poor parenting" or a child's "lack of discipline." Understanding the medical history, which includes early biological explanations, directly refutes these claims. The neurodiversity movement helps dispel the idea that ADHD is a "mental illness" by positioning it as a difference in brain wiring—a crucial distinction for families and individuals seeking clarification, and often a key hidden intent.

Q7: Where can I find more resources on the neurodiversity movement and ADHD?

For more information, consider exploring reputable organizations like CHADD, ADDA, and websites that focus on neurodiversity advocacy. Academic institutions like Caltech also offer valuable resources. We recommend exploring our "Further Reading" section for curated links.

This journey through history reminds us that understanding ADHD is an ongoing process of discovery, shaped by science, culture, and most importantly, the lived experiences of individuals. By arming yourself with this comprehensive perspective, you're better equipped to cut through the noise, challenge outdated views, and advocate for an inclusive future where all minds are valued.