It’s a familiar scenario for many with ADHD: a deadline that felt comfortably distant suddenly slams into the present with an almost physical jolt. The emotional urgency is immediate, overwhelming, and disproportionate. Or perhaps a minor annoyance escalates into an all-consuming rage that feels like it will never end. These aren't just isolated emotional outbursts; they're often deeply rooted in how the ADHD brain perceives and processes time.

You're here because you’re evaluating solutions for these critical emotional management challenges, seeking to understand the "why" behind the "what" and find strategies that truly resonate with the unique way your ADHD brain works. This exploration isn't about generic coping mechanisms; it’s about delving into the novel and insightful connection between time perception and emotional regulation in ADHD, equipping you with the understanding and tools to navigate this complex inner landscape. We'll show you how a deeper understanding of this nexus can transform your approach to emotional well-being.

The ADHD "Time Warp": More Than Just Being Late

The concept of "time blindness" in ADHD is often discussed in terms of missed appointments or forgotten tasks. Yet, its impact on emotional management is far more profound. For those with ADHD, time isn't a continuous, flowing river; it's often perceived as disparate islands of "now" and "not now," a phenomenon known as temporal myopia or "now or not now" thinking. This isn't laziness; it's a neurological reality, a "focal symptom" of ADHD. Research from PubMed Central highlights time perception itself as a central symptom for adults with ADHD, indicating it's not a secondary issue but a core component of the condition.

This distorted perception feeds what’s called temporal discounting, where immediate rewards and consequences are valued far more heavily than future ones. If something isn't happening right now, its emotional weight significantly diminishes. This means the looming dread of a future deadline might not register until it's practically upon you, at which point it triggers an intense, urgent emotional response.

The Emotional Urgency of Deadlines

Consider a project deadline two weeks out. For a neurotypical brain, this is a gradual descent, allowing for phased planning and emotional preparation. For someone with ADHD experiencing time blindness, those two weeks exist in the nebulous "not now." Suddenly, it’s tomorrow, and the project has vaulted into the "NOW" category. The brain interprets this immediate necessity as a crisis, triggering an intense fight-or-flight response. The emotional urgency isn't about the task itself but the sudden, compressed perception of available time, leading to panic, anxiety, or acute stress. This isn't just about missing a deadline; it's about the emotional whiplash of transitioning from zero urgency to absolute crisis in an instant.

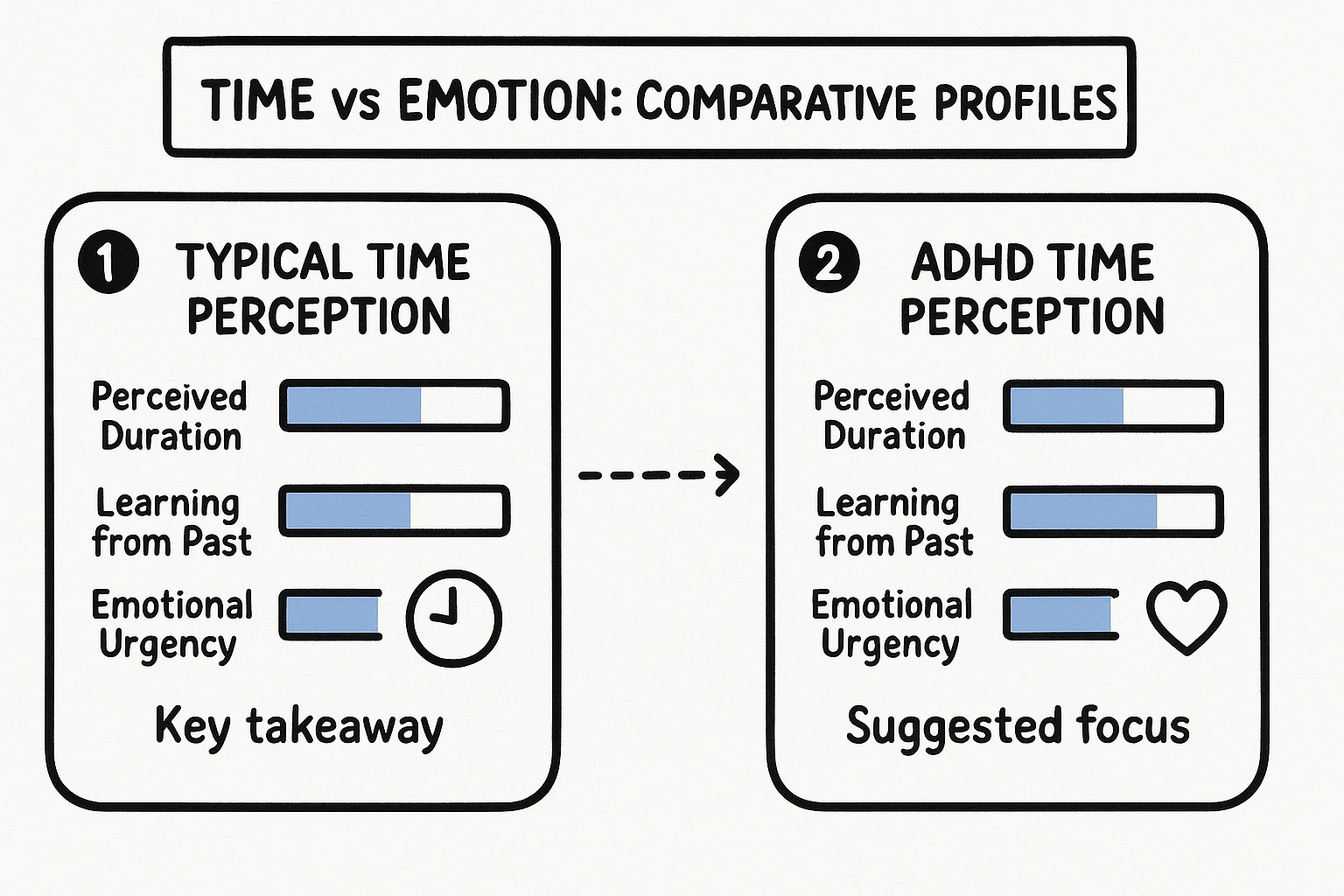

Comparing Symptom Profiles: Time Perception & Emotional Urgency

The chart above illustrates how distorted time perception directly amplifies emotional responses and limits the ability to integrate past experiences. This is not simply a matter of poor planning; it’s a fundamental difference in how time and emotion interact in the ADHD brain.

The Emotional Echo Chamber: How Time Distortion Amplifies Feelings

Beyond deadlines, this distorted time perception creates significant challenges for emotional regulation, making emotions feel more intense, longer-lasting, and harder to learn from. Emotional dysregulation (ED) is recognized as a core feature of ADHD, linked to significant functional impairment and heightened risk for co-occurring conditions like anxiety and depression. The American Psychological Association (APA) emphasizes that for individuals with ADHD, ED can manifest as irritability, a short fuse, or being easily overexcited.

Difficulty Learning from Past Emotional Experiences: The "Reset Button" Effect

One of the most insidious effects of time blindness on emotions is the difficulty in learning from past emotional experiences. Imagine you had an intense argument last week that left you reeling. A neurotypical brain can readily access that memory, recall the uncomfortable feelings, and use it to inform future interactions or practice different responses. For someone with ADHD, however, last week’s argument can often feel like a distant, almost separate event, stripped of its emotional resonance. Each new emotional trigger feels novel, as if encountered for the first time. The brain struggles to retrieve the emotional timeline, making it hard to apply lessons learned about triggers or coping mechanisms. This "reset button" effect means emotional patterns can repeat, leaving individuals feeling stuck and frustrated.

The Feeling That Intense Emotions Will 'Never End'

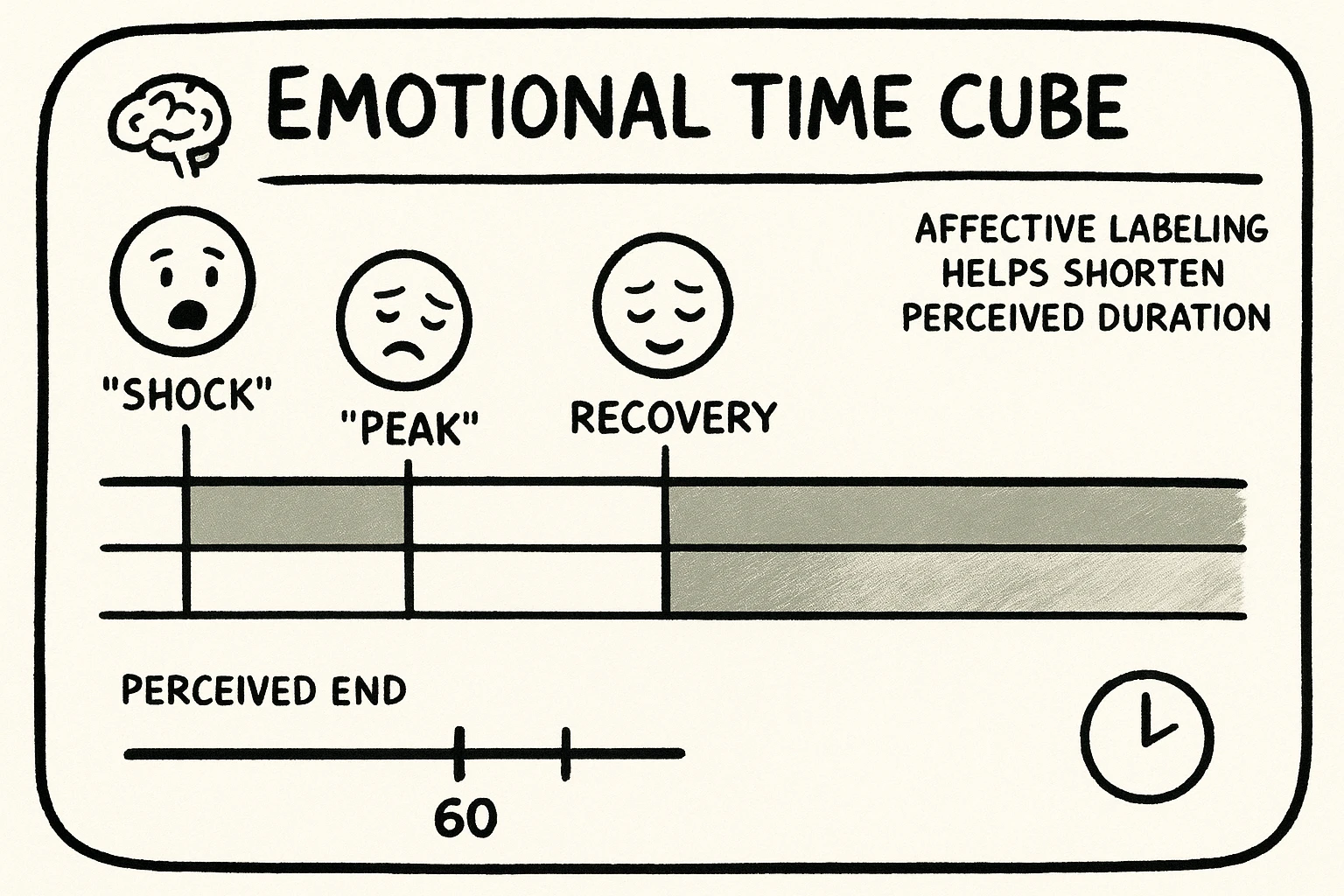

When an intense emotion—be it anger, sadness, or anxiety—strikes, the individual with ADHD often struggles to perceive its finite nature. Because time is not experienced as a continuous flow, an overwhelming feeling can feel like it will last indefinitely. There’s no natural mental timer ticking down, providing reassurance that "this too shall pass." This absolute perception during an emotional peak significantly amplifies distress, making the experience even more agonizing. It’s akin to being trapped in a moment without a clear exit, because the concept of an "end" or "recovery" is temporally blurred.

This visualization helps to normalize the emotional journey, emphasizing that even intense emotional states have a natural progression towards recovery. For ADHD brains, explicitly acknowledging and visualizing these phases can be a powerful tool against the feeling of permanence.

Chronic Lateness and its Hidden Emotional Burden

Beyond personal distress, time blindness often manifests as chronic lateness or missing obligations. The outward perception might be disorganization or disrespect, but the inner experience is usually profound shame, guilt, and self-blame. The initial "not now" perception of needing to leave shifts abruptly to "NOW," sparking a mad dash and leading to inevitable lateness. The repeated cycle erodes self-esteem and strains relationships. The individual is left grappling with the emotional weight of failures perceived as moral failings, rather than symptoms of a neurological difference. The constant internal narrative of "I should have known better" or "I always do this" feeds into a deeper sense of inadequacy.

The Brain Science Behind the Link (Simplified)

At the heart of this time-emotion nexus lies the intricate wiring of the ADHD brain. Both time perception and emotional regulation are heavily reliant on executive functions—the brain's command center for planning, working memory, attention, and impulse control. Impairments in these functions, particularly the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) and orbitofrontal cortex (OFC), found in ADHD, contribute to both time estimation challenges and emotional dysregulation.

Dopaminergic pathways also play a crucial role. These pathways are involved in reward processing and motivation, and their atypical functioning in ADHD can exacerbate the "now or not now" thinking, prioritizing immediate gratification over future planning. When the brain struggles to accurately predict future rewards or consequences, it struggles to emotionally invest in them, leading to a focus on the immediate sensation. This neurological interplay creates a complex feedback loop where impaired executive functions hinder accurate time perception, which in turn amplifies emotional reactivity and reduces the capacity for emotional regulation.

"Future-Pacing" Your Emotions: Bridging the Time-Emotion Gap in ADHD

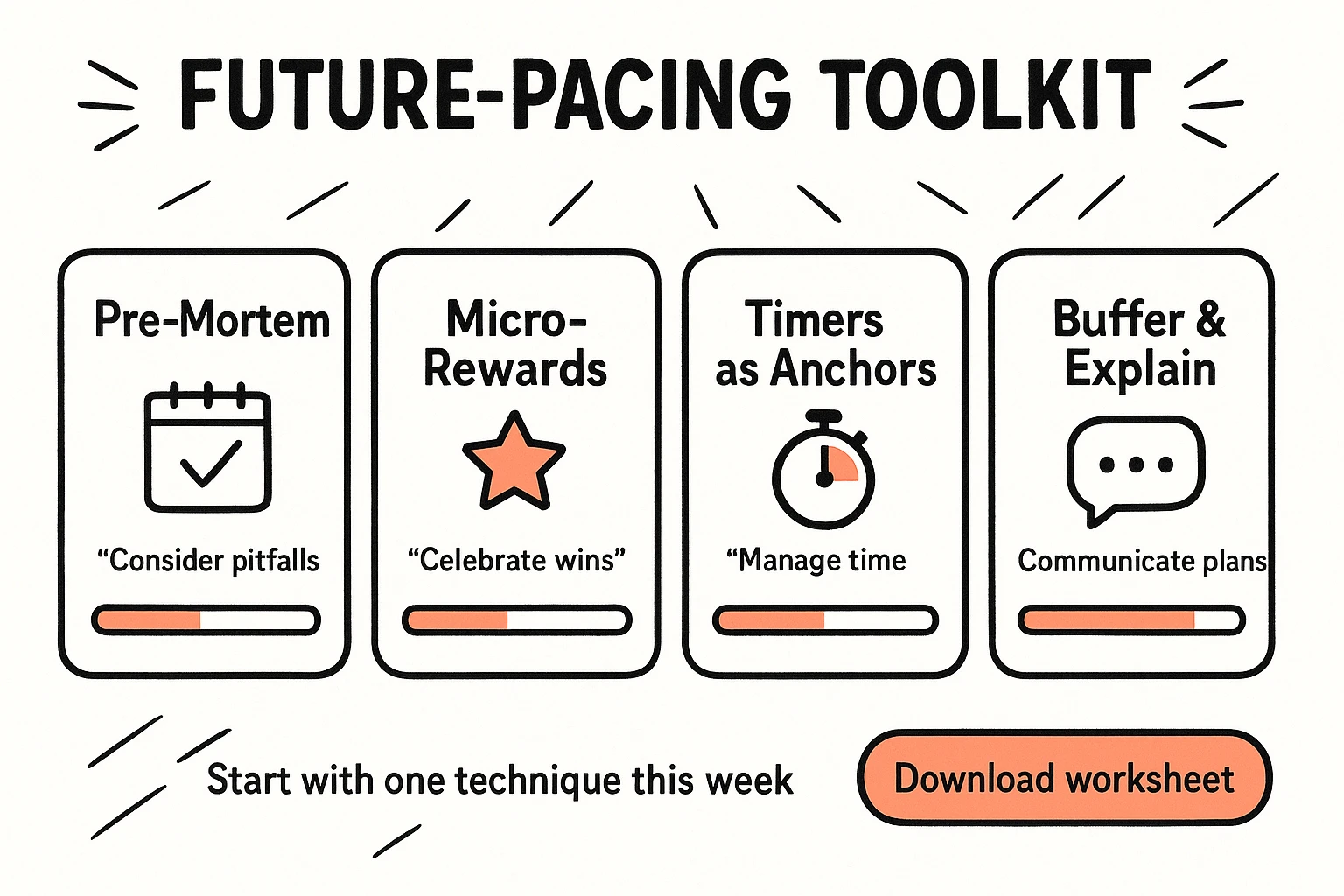

To navigate this landscape, we need strategies that specifically address the interaction between time perception and emotional management. Generic self-help often falls short because it doesn't account for the unique temporal challenges of ADHD. Here, we offer approaches designed for the ADHD brain.

Strategy 1: Creating Emotional Time Cubes

This strategy counters the "never-ending" feeling of intense emotions by introducing a concrete, temporal structure. Instead of letting an emotion wash over you indefinitely, you assign it a mental "box" with a clear beginning and end.

How it works:When an intense emotion begins, mentally or physically label it. "This is a wave of anger, starting now." Set a short, realistic timer (e.g., 5-10 minutes). During this time, allow yourself to feel the emotion without judgment, perhaps engaging in a grounding technique. When the timer goes off, consciously acknowledge the change in time and emotion. Remind yourself: "That intense peak has passed. I am entering the recovery phase." This helps to externalize the passage of time during emotional states, making the duration tangible and countering the perception of endlessness. Repeated practice builds a mental archive of emotional arcs, which aids in future emotional recall and regulation.

Strategy 2: "Pre-Mortem" Emotional Rehearsal

This powerful technique borrows from project management and adapts it for emotional preparedness, directly addressing the emotional urgency of looming deadlines.

How it works:Before a known stressor (e.g., a challenging conversation, an approaching deadline, a public speaking event), engage in a "pre-mortem" exercise. Visualize the event as if it has already gone wrong emotionally. What specific emotions might arise? (Panic, frustration, shame). How intense might they be? Then, mentally rehearse your desired emotional response and coping mechanisms. For instance, if you anticipate panic before a deadline, envision yourself taking deep breaths, reminding yourself of past successes, or utilizing a specific de-escalation technique. This pre-emptive mental walk-through helps to build a more robust emotional "time-map" for future events, reducing the shock of sudden emotional urgency. It essentially trains your brain to "future-pace" its emotional responses.

Strategy 3: Micro-Future Rewards

This strategy leverages ADHD's inherent temporal discounting by breaking down tasks and emotional challenges into small, immediately rewarding steps, fostering emotional stability.

How it works:For any task or emotional challenge that feels overwhelming due to its perceived distance or complexity, define tiny, achievable sub-steps. Attach a micro-reward to each immediate completion. For example, if you need to tackle a daunting report (leading to anxiety), the first "micro-step" might be "open the document for 5 minutes," followed immediately by a small, dopamine-boosting reward (e.g., 2 minutes of a favorite podcast, a stretch break). For an emotional regulation challenge, the "micro-future reward" could be the immediate positive feeling of having paused before reacting, acknowledged a feeling without acting on it, or the pride of using an emotional regulation skill. By creating frequent, small "now" rewards, you gradually build momentum and teach your brain that engaging with the "future" (even the near-future) can be pleasurable, thereby overcoming the paralysis of temporal discounting. This re-wires the emotional response to effort and future-oriented action.

Practical Strategies Checklist

This checklist provides a comparative glance at the strategies, helping you select one to implement this week and track your adoption pace. The key is to start small and build consistency.

Strategies for Managing Chronic Lateness and its Emotional Fallout

Chronic lateness isn't a moral failing; it's a symptom. Addressing the emotional burden requires both practical time management adjustments and deep self-compassion.

The "Buffer & Explain" Method

Recognize that your brain will consistently underestimate the time needed for tasks. Build in absurdly generous buffers. If something takes 15 minutes, tell yourself it takes 45. For leaving the house, add an extra 20-30 minutes after you think you're ready.

Crucially, learn to communicate this reality to trusted individuals. Instead of apologies laden with self-recrimination, offer honest, empathetic explanations: "My brain struggles with time, so I'm often not as punctual as I intend to be. I'm working on it with strategies, and it means a lot to me that you understand." This reframes the issue and seeks understanding rather than just forgiveness, while also setting external accountability.

Self-Compassion for the "Time Thief"

The internal shame associated with lateness can be crushing. Understand that your experiences are rooted in real neurological differences, not a lack of effort or care. Practice self-compassion. When you are late, acknowledge the feeling of disappointment or frustration, but counter the automatic self-criticism. Instead of "I'm so useless," try "This is a challenge my ADHD presents, and I'm doing my best to manage it." This gentle self-talk helps to decouple your worth from your punctuality.

Externalizing Accountability

For essential time-sensitive tasks or commitments, externalize accountability. This could mean working with an ADHD coach who specializes in time management, setting public commitments with colleagues, or using accountability partners. The external structure helps to concretize time and its consequences, providing the scaffolding your internal executive functions might struggle to maintain.

Mindfulness of "Timed-Emotions": Cultivating Temporal Awareness for Emotional Stability

Mindfulness is often recommended for emotional regulation, and for ADHD, it needs a specific temporal focus. Rather than just "presence," it’s about observing the duration and transition of emotional states.

Adapting Mindfulness for ADHD

Traditional mindfulness focuses on simply observing the present moment. For ADHD, this can be adapted to observe the flow of time during an emotional state. Instead of just "I feel anxious," try "I am aware of this anxiety, and I'm noticing how it changes over the next minute, then the next." This emphasizes the transient nature of feelings.

Use visual or auditory cues. Set a gentle timer for 3-5 minutes during an emotional peak and use that time to mindfully notice the sensations, thoughts, and physiological changes. When the timer sounds, it serves as a temporal anchor, signaling both the passage of time and an opportunity to shift focus or engage a new strategy.

"Now & Next" Emotional Check-ins

Instead of the broad "Now or Not Now" perception, implement structured "Now & Next" emotional check-ins. When you realize you're feeling an intense emotion, ask yourself: "What emotion am I feeling right now? What steps can I take to support myself in the next segment of time (e.g., next 15 minutes, next hour)?" This small shift helps to create a structured temporal awareness around emotional management, breaking the cycle of being overwhelmed by static "now" feelings.

Leveraging Technology & Support for Integrated Management

While personal strategies are crucial, modern tools and professional support can significantly enhance your ability to bridge the time-emotion gap.

- Advanced Time Management Apps with Emotional Integration: Look for apps that don't just track tasks but allow for notes on emotional states during tasks, or offer features like timed "emotional breaks" or "mindfulness moments." Think about how a tool could help you externalize and visualize the duration of your emotional experiences.

- ADHD Coaching focused on Time-Emotion Linking: Seek out coaches who understand the intricate connection between time perception and emotional dysregulation. They can help you personalize these strategies and provide much-needed accountability and objective feedback regarding your temporal awareness and emotional responses.

- Therapies (CBT/DBT) with a "Temporal Focus" Adaptation: Therapies like Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) and Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT) are highly effective for emotional dysregulation. When working with a therapist, explicitly discuss your challenges with time perception and how it impacts your emotional states. A therapist can help you adapt these techniques to specifically address your "time-blind" emotional experiences, perhaps by integrating the "Emotional Time Cubes" or "Pre-Mortem Emotional Rehearsal" into your therapeutic work.

FAQs: Addressing Your Evaluation Criteria

Q: Why do traditional time management strategies often fail people with ADHD?

Traditional strategies often assume a linear perception of time and consistent executive function, which are precisely what ADHD impacts. They typically focus on external organization without addressing the internal "now or not now" thinking or the emotional toll of time blindness. Our integrated approach helps by targeting the root temporal issues that lead to emotional dysregulation.

Q: Is "emotional dysregulation" just another term for being oversensitive?

No. While people with ADHD can be sensitive, emotional dysregulation is a specific challenge in managing the intensity and duration of emotional responses. It's not about being "too sensitive" but about the brain's impaired ability to regulate emotions, often manifesting as intense reactions disproportionate to the trigger. The connection to time perception further explains why these reactions can feel so overwhelming and long-lasting.

Q: How can I explain "time blindness" and its emotional impact to friends or family who don't understand?

The key is to use metaphors and analogies that highlight the neurological difference without implying a lack of effort. You can explain that your brain doesn't naturally keep track of time passing, making future events feel distant until they are immediate, causing a sudden emotional rush. You could say, "My brain's internal clock runs differently, so I often experience deadlines as sudden emergency alarms, triggering intense stress, rather than a gradual build-up." Sharing resources like this article can also foster understanding.

Q: Can medication help with the time-emotion link?

Yes, often. ADHD medications (stimulant and non-stimulant) can improve executive functions, which in turn can lead to better time perception and impulse control. By enhancing these underlying cognitive processes, medication can indirectly help to reduce the intensity and frequency of emotional dysregulation stemming from time-related issues. However, medication is often most effective when combined with behavioral strategies and therapy.

Q: How is this approach different from just "being more mindful"?

While mindfulness is part of the solution, our approach emphasizes temporal mindfulness. Instead of general presence, it's about explicitly observing the passage and structure of time during emotional experiences. Techniques like "Emotional Time Cubes" and "Now & Next" check-ins are tailored to the ADHD brain's specific struggles with time, providing external scaffolding and a purposeful framework that generic mindfulness might lack for someone grappling with significant time blindness.

Your Path Forward: Building a More Emotionally Stable Future

Understanding the profound interplay between ADHD's altered time perception and emotional dysregulation is a game-changer. It shifts the narrative from personal failing to neurological challenge, opening the door to truly effective strategies. By recognizing how your "time warp" fuels emotional urgency, hinders learning from past feelings, and makes intense emotions feel eternal, you gain the power to intervene.

The "Future-Pacing" methods, targeted strategies for chronic lateness, and adaptations of mindfulness we've discussed offer concrete pathways to cultivate greater emotional stability and self-compassion. This isn’t a quick fix, but a journey of understanding and intentional practice, guided by insights tailored to the ADHD brain.

Your next steps are clear: choose one strategy, perhaps the "Emotional Time Cubes" or "Pre-Mortem Emotional Rehearsal," and commit to practicing it this week. Observe the subtle shifts in your emotional landscape. Consider exploring our resources on ADHD coaching or finding a therapist specializing in ADHD-informed CBT/DBT to further personalize these powerful tools. Embrace this deeper understanding, and start building a more predictable, less emotionally turbulent future.