The words we use don't just describe reality; they shape it. For too long, the language surrounding Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) has been steeped in misunderstanding, deficit-based thinking, and outright stigma. As you navigate the complex landscape of understanding ADHD—whether for yourself, a loved one, or simply to be a more informed ally—the terminology you encounter can either empower or disempower. It can foster connection or perpetuate harmful stereotypes.

At My ADHD, we understand that language is a powerful tool, capable of building bridges of empathy or erecting walls of isolation. In this comprehensive guide, we'll deconstruct historically negative terms, analyze their profound impact, and equip you with ADHD-affirming alternatives. Our goal is to provide a trusted resource that not only clarifies the nuances of neurodiversity-affirming language but also empowers you to confidently advocate for a more respectful, strengths-based narrative. This isn't just about changing words; it's about shifting perceptions and reclaiming identity.

The Power of Words: Shaping Perceptions of ADHD

Think about the immediate imagery evoked by common phrases related to ADHD. Do they conjure images of disorganization, lack of focus, or perhaps something more profound and unique? The language we use, often unconsciously, significantly influences how we perceive ourselves and others. Harmful ADHD terminology profoundly impacts self-perception and mental health, leading to decreased self-esteem, increased social isolation, and exacerbated psychological distress, as research has consistently shown. This isn't theoretical; it's a lived reality for many, underscoring the critical need for language reform to protect mental well-being.

This guide will systematically dismantle the linguistic barriers that have historically obscured a true understanding of ADHD. We'll trace the roots of these damaging terms, clarify the modern neurodiversity framework, provide actionable language choices, and empower you to effectively challenge misinformation and advocate for change.

The Echoes of the Past: A History of Harmful ADHD Terminology

To truly appreciate the power of affirming language, we must first understand the historical context of the terms we're trying to move beyond. The journey of ADHD terminology reflects a shifting understanding of neurobiology, psychology, and societal attitudes. Early psychiatric labels, often rooted in moral judgments or a primitive understanding of the brain, laid a foundation for stigma that persists today.

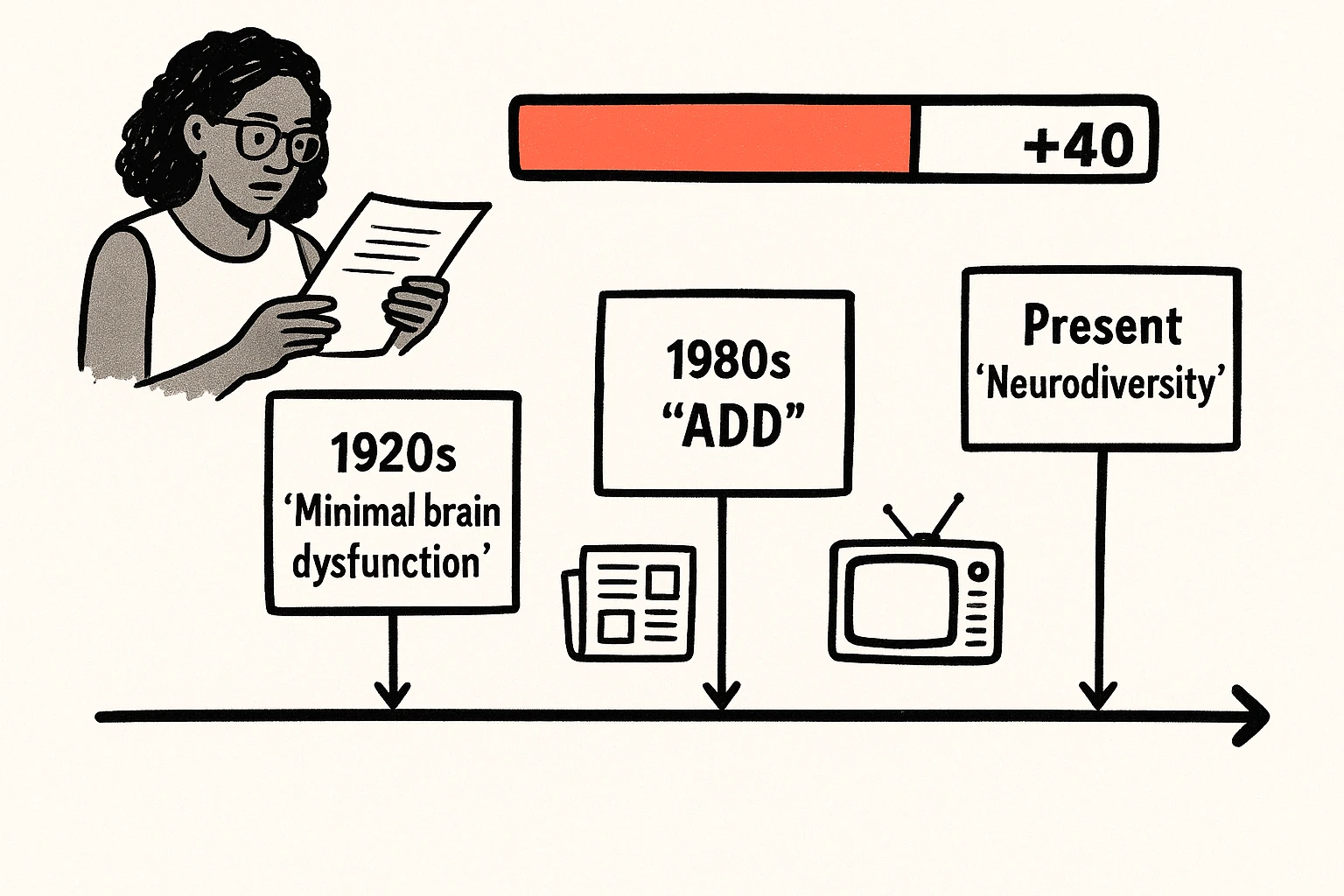

Historically, conditions now recognized as ADHD were once dismissed as "moral deficiency," "minimal brain damage," or later, "minimal brain dysfunction" (MBD) in the mid-20th century. These terms, while seemingly clinical at the time, directly fostered negative stereotypes and a deeply deficit-based way of thinking. They implied inherent flaws rather than neurobiological differences. Even the shift from "ADD" (Attention Deficit Disorder) to "ADHD" (Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder) marked an important, albeit still evolving, understanding of its varied presentations.

The psychological impact of these historical labels cannot be overstated. When society views a neurotype through a lens of "damage" or "deficiency," individuals often internalize this shame, impacting their self-identity and sense of belonging. Racial disparities further compound this issue, with children of color facing compounded stigma and disparities in diagnosis and treatment. For example, lower medication use rates among Black (36%) and Latino (30%) children compared to White children (65%) highlight how societal language and perceptions intersect with systemic inequalities. Understanding this lineage helps us see how deeply ingrained some of these harmful perceptions are.

Here's a timeline illustrating this evolution and the marked shift towards neurodiversity-affirming language:

A clear timeline mapping harmful ADHD labels to modern neurodiversity language, showing the cultural shift toward strengths-based framing.

This timeline clearly shows our journey from pathologizing differences to acknowledging the rich tapestry of human neurology.

Defining Neurodiversity: Understanding the Framework

Central to reclaiming ADHD language is understanding the concept of neurodiversity. This framework views neurological variations—like ADHD, autism, dyslexia, and Tourette's syndrome—as natural and valuable forms of human diversity, rather than deficits or disorders.

Let's clarify some key terms:

- Neurodiversity: This is an umbrella term referring to the vast, natural variation in human brains and cognitive functioning. It's a concept, like biodiversity, acknowledging that all human brains are diverse.

- Neurodivergent: This describes an individual whose brain functions in ways that diverge significantly from the dominant societal standards of "typical." This includes people with ADHD, autism, dyslexia, etc.

- Neurotypical: This describes an individual whose brain functions in ways that fall within the dominant societal standards of "typical."

- Neurotype: This refers to a specific type of neurological wiring, e.g., an ADHD neurotype, an autistic neurotype.

The discussion often arises around whether to use "disorder," "condition," or "neurotype." While "disorder" is still the clinical diagnostic term, many advocates prefer "condition" or "neurotype" as they carry less cultural baggage of pathology and dysfunction. The World Federation of ADHD, for instance, emphasizes reducing stigma by careful language choices, often preferring descriptions that focus on differences rather than deficits. This shift aligns with the social model of disability, which posits that disability is often created by societal barriers and attitudes, rather than an inherent defect in the individual. Language that highlights differences rather than disorders helps to dismantle these barriers.

The Weight of Words: Impact of Deficit-Based vs. Strengths-Based Language

The language we choose has a profound psychological and social impact. Using deficit-based language — terms like "broken," "deficient," or phrases like "suffers from ADHD" or "ADHD is an excuse" — reinforces negative stereotypes. This type of framing often leads to internalized shame, reduced self-esteem, and disengagement. It focuses on perceived shortcomings rather than unique abilities, fostering an environment where individuals with ADHD feel like they need to "fix" themselves to conform.

Consider this: research shows that deficit-based language leads to internalized shame and disengagement, while strengths-based language fosters identity, hope, and psychological well-being. It reframes neurodivergence as a form of human diversity, crucial for positive self-identity and improving therapeutic outcomes. The Australasian ADHD Professionals Association (AADPA) guide effectively demonstrates this by directly connecting language choices to reducing stigma and psychological harm.

Conversely, embracing strengths-based language highlights unique cognitive styles and potential advantages. Instead of "attention deficit," we might talk about "differences in executive function." Instead of focusing solely on challenges, we can celebrate creativity, resilience, hyperfocus, and divergent thinking as aspects of the ADHD neurotype. Real-life examples from our community, though often shared anonymously, consistently affirm that language recognizing these strengths significantly improves self-perception and fosters a sense of empowerment. It validates their experiences and encourages them to view their neurotype as integral to who they are, rather than a flaw to be overcome.

The ADHD-Affirming Language Playbook: Your Practical Guide

Navigating the nuances of ADHD-affirming language can feel challenging, especially with so much conflicting information. This playbook provides clear, actionable guidance to help you make informed and respectful choices.

The goal isn't rigid prescriptivism but rather fostering mindful communication. As ADHD UK's language guide highlights, personal preference is key. While many prefer person-first language ("person with ADHD"), others embrace identity-first language ("ADHDer"), seeing their neurotype as an integral part of their identity. Both are valid.

Below is a practical guide:

Side-by-side comparison of harmful versus affirming ADHD language with a stigma impact indicator—clear guidance for choosing respectful words.

Navigating Nuances

- "ADHD as a Superpower": This phrase is increasingly common, highlighting strengths like hyperfocus and creativity. While well-intentioned, it should be used with caution, as ADHD also presents significant challenges. It's important not to invalidate the struggles by overly romanticizing the condition. ADHD UK discusses this nuance, emphasizing that while there are strengths, it's also a disability that can require significant support.

- "A little bit ADHD": This phrase trivializes a genuine neurodevelopmental condition. ADHD is a clinical diagnosis, not a descriptor for occasional forgetfulness or disorganization. Explaining the clinical reality rather than dismissing this phrase can be more effective.

- Communication Strategies: When talking to doctors, teachers, family, or peers, focus on respectful dialogue. If someone uses outdated terminology, politely offer an alternative and explain why it's preferred without shaming them. Education is key.

Fighting Stigma Through Words: Advocacy and Community Action

The battle against stigma isn't just about individual word choices; it's also about collective action and advocacy. Media, in particular, plays a significant role in perpetuating stereotypes, often resorting to caricatures or focusing solely on negative portrayals. By consciously adopting affirming language, we can influence public discourse.

Empowering Your Advocacy

Here are steps you can take to become an advocate for language change:

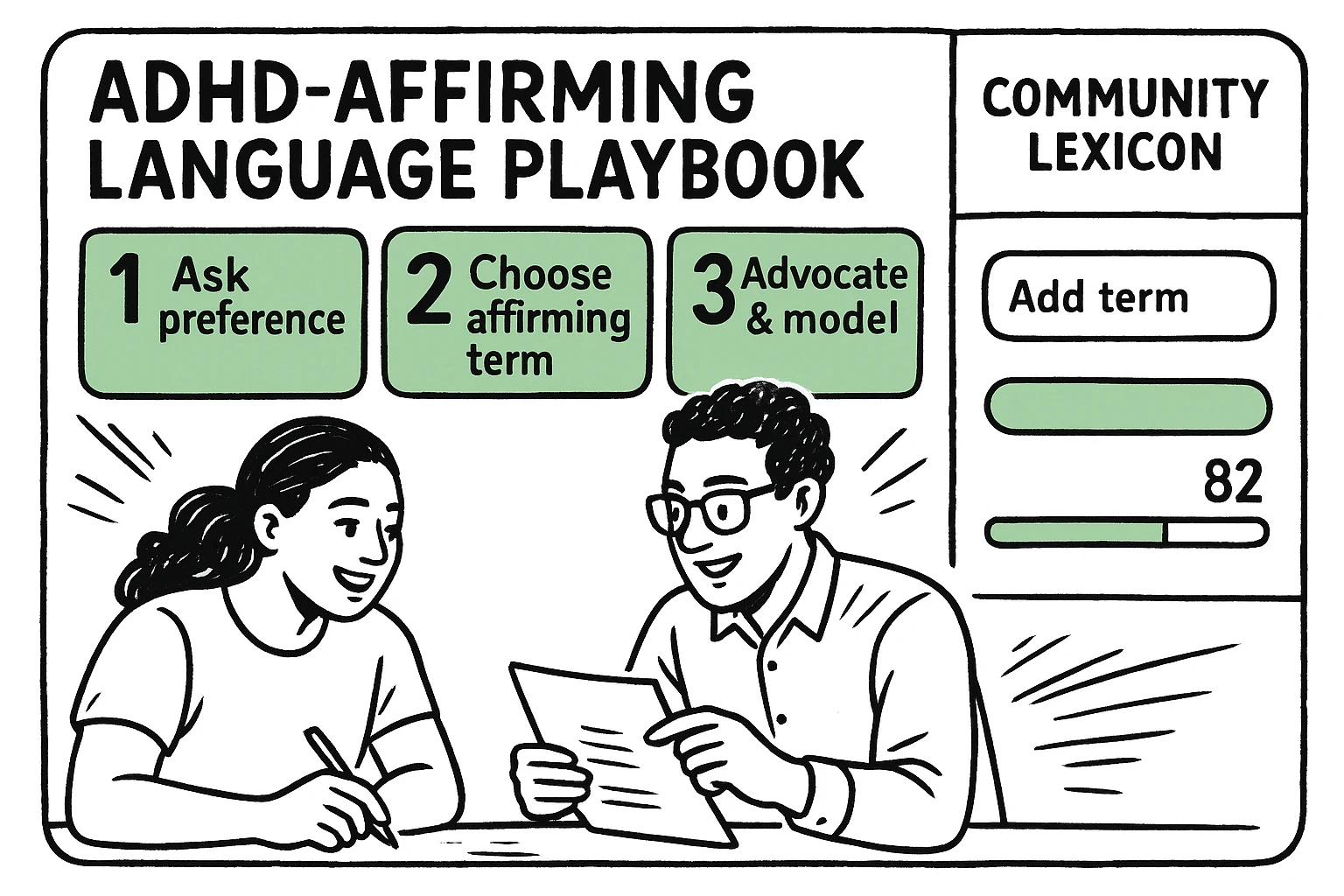

A practical playbook with three clear steps and a community lexicon panel—designed to help readers adopt, model, and advocate for affirming language.

- Educate Yourself: Continuously learn and refine your understanding of ADHD and neurodiversity. The more informed you are, the more effectively you can respond to misinformation.

- Model Affirming Language: Be the change you wish to see. Consistently use strengths-based, person-first (or identity-first, if preferred) language in your daily interactions.

- Advocate Respectfully: When you encounter harmful or outdated language, choose moments to gently educate others. Share resources like this guide. Confronting stigma directly but kindly can be incredibly impactful. For instance, if a colleague refers to someone as "an ADHD case," you might say, "I find it more empowering to say 'a person with ADHD' or 'an ADHDer.' What do you think?"

Community-Curated Positive ADHD Language Dictionary/Lexicon

Beyond expert-curated lists, the ADHD community itself is a vibrant source of evolving, affirming language. We encourage you to contribute to our growing Community-Curated Positive ADHD Language Dictionary. This interactive tool allows users to submit terms, explain their meaning and impact, and upvote or downvote existing entries. Terms like "neurospicy," while informal, reflect a joyful reclaiming of identity for many. This lexicon helps us understand the nuanced and often humorous ways the community expresses its unique experiences.

Conclusion: Reclaiming Our Narrative – A Path to Empowerment

The journey of deconstructing harmful ADHD terminology is an ongoing one, but its destination is clear: a world where language fosters understanding, empathy, and empowerment. By thoughtfully choosing our words, we challenge stigma, honor individual experiences, and pave the way for a more inclusive future for those with ADHD.

Every conversation, every article, every personal choice of language contributes to this vital shift. We encourage you to embrace this ADHD-affirming language playground, apply what you've learned, and join us in advocating for a narrative that truly reflects the complexity, beauty, and strength of the ADHD neurotype.

The power to reshape perception is in our words. Let's use them wisely and compassionately.

Frequently Asked Questions about ADHD Language

Q1: Why is "person-first language" (e.g., "person with ADHD") often preferred over "identity-first language" (e.g., "ADHDer")?

Person-first language emphasizes the individual before their condition, aiming to reduce dehumanization and stigma by highlighting that a person is not defined solely by their diagnosis. However, preferences vary. Many in the neurodivergent community, including some ADHDers, prefer identity-first language because they view their neurotype as an integral and inseparable part of their identity, not something they "have." It's best to respect individual preference: if someone identifies as an "ADHDer," use that term. If they prefer "person with ADHD," use that.

Q2: What's wrong with saying someone "suffers from ADHD"?

The phrase "suffers from ADHD" implies that ADHD is inherently a source of pain or misery that defines someone's existence. While ADHD can certainly present significant challenges and cause distress, framing it purely in terms of suffering can be disempowering and deficit-based. Preferable alternatives like "a person with ADHD" or "an individual who experiences ADHD" acknowledge the condition without imposing a narrative of constant suffering. This aligns with the understanding that language impact self-perception and mental health.

Q3: Why is "ADHD is a superpower" sometimes seen as problematic?

While the sentiment behind "ADHD is a superpower" can be positive, aiming to highlight strengths like creativity, energy, and hyperfocus, it can be problematic if it dismisses or minimizes the very real challenges and struggles that individuals with ADHD face daily. ADHD is a diagnosed condition that can significantly impact executive functions, learning, and daily life. Overly romanticizing it risks invalidating the need for support, accommodations, or treatment, and can gloss over the experiences of those who struggle profoundly. It's more accurate to say that people with ADHD often possess unique strengths, but it's not a "superpower" without its significant complexities.

Q4: How can I politely correct someone who uses outdated or harmful ADHD language?

The key is often gentle education rather than confrontation. You might say something like, "I've learned that using [outdated term] can sometimes carry negative connotations or make people feel [impact, e.g., 'stigmatized']. Many people with ADHD prefer [alternative term] because it's more accurate and respectful." Offer a brief explanation of why the alternative is better. Sharing resources like this guide can also be helpful. The goal is to inform and encourage new habits, not to shame.

Q5: Is the term "Attention Deficit Disorder" (ADD) still used?

Clinically, the term "Attention Deficit Disorder" (ADD) is largely outdated. In 1994, the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV) formally incorporated all presentations of attention difficulties, with or without hyperactivity, under the umbrella term "ADHD" (Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder). It then categorized presentations into "predominantly inattentive," "predominantly hyperactive-impulsive," and "combined." While some individuals still self-identify as having "ADD" (often referring to the predominantly inattentive presentation), the current clinical diagnosis is ADHD.