Navigating grief is profoundly challenging for anyone, but if you have ADHD, that path often feels like a chaotic, winding road with unexpected detours and intense emotional spikes. You might find yourself asking, "Is this how everyone grieves, or am I doing it 'wrong'?" The truth is, your neurodivergent brain processes loss in uniquely intense ways, leading to experiences that often don't align with conventional ideas of grieving.

Here at myadhd.co, we understand that journey. We know that the traditional five stages of grief can feel like an impossible checklist when your internal world is already a "beautifully chaotic, endlessly fascinating, mildly exhausting mental internet." This piece isn't about fixing your grief; it's about validating your experience, helping you understand why it feels different, and empowering you with neurodivergent-friendly strategies to find your authentic path to healing.

The Neurodivergent Grief Experience: Why it Feels Different

Your brain is wired differently, and that's not a flaw—it's a characteristic that shapes every aspect of your life, including how you cope with profound loss. Understanding these differences is the first step toward self-compassion and effective healing.

Emotional Overload & Dysregulation: The ADHD Brain's Intense Reactivity

One of the most defining aspects of ADHD grief is its sheer intensity. You might feel emotions with an almost overwhelming force, swinging quickly between deep sadness, anger, confusion, and even moments of unexpected calm or hyperfocus. This isn't a sign of weakness; it's a direct reflection of your brain's unique wiring.

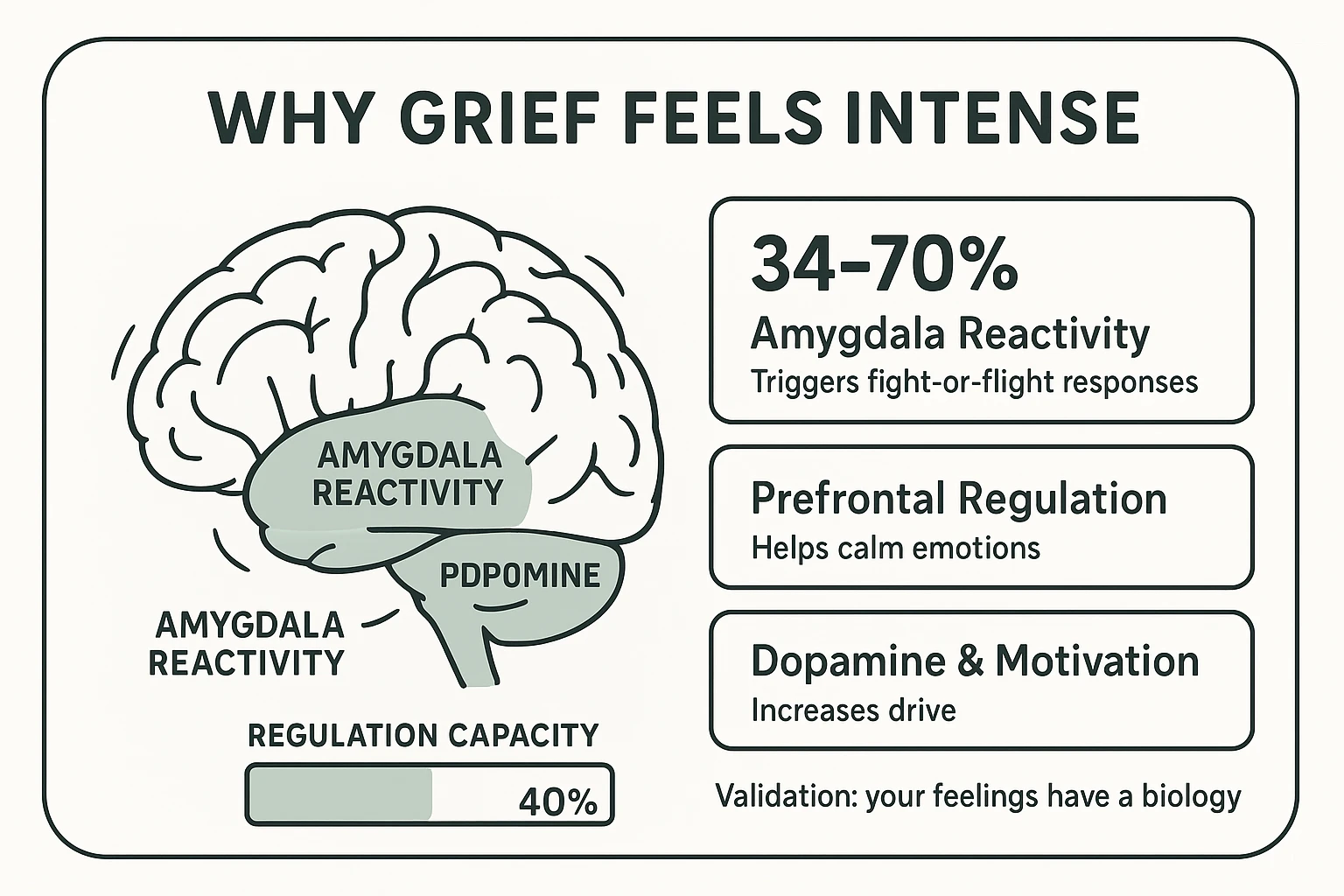

Research indicates that emotional dysregulation (ED) is a significant and prevalent—affecting an estimated 34-70% of adults—and evolving characteristic of ADHD, increasingly recognized as a core symptom rather than just a co-occurring condition. This heightened reactivity stems from differences in brain structure and function, particularly involving the amygdala (the brain's emotion center) and the prefrontal cortex (responsible for executive functions like emotional regulation). Your dopamine pathways, which play a crucial role in regulating mood and emotional responses, also function differently. This neurobiological foundation means that your brain is simply more prone to intense emotional responses and has a harder time modulating them. It’s why one moment you might feel completely numb, and the next, a flood of despair.

It's crucial to acknowledge this inherent neurological difference. When emotions feel like "too much," it's not a personal failing; it's your brain responding to an immense stressor in its own way. This means you’re not "broken" for feeling such profound pain; you're simply experiencing grief through a neurodivergent lens.

Time Blindness & Non-Linear Grieving: "Yesterday, Today, and Six Months Ago"

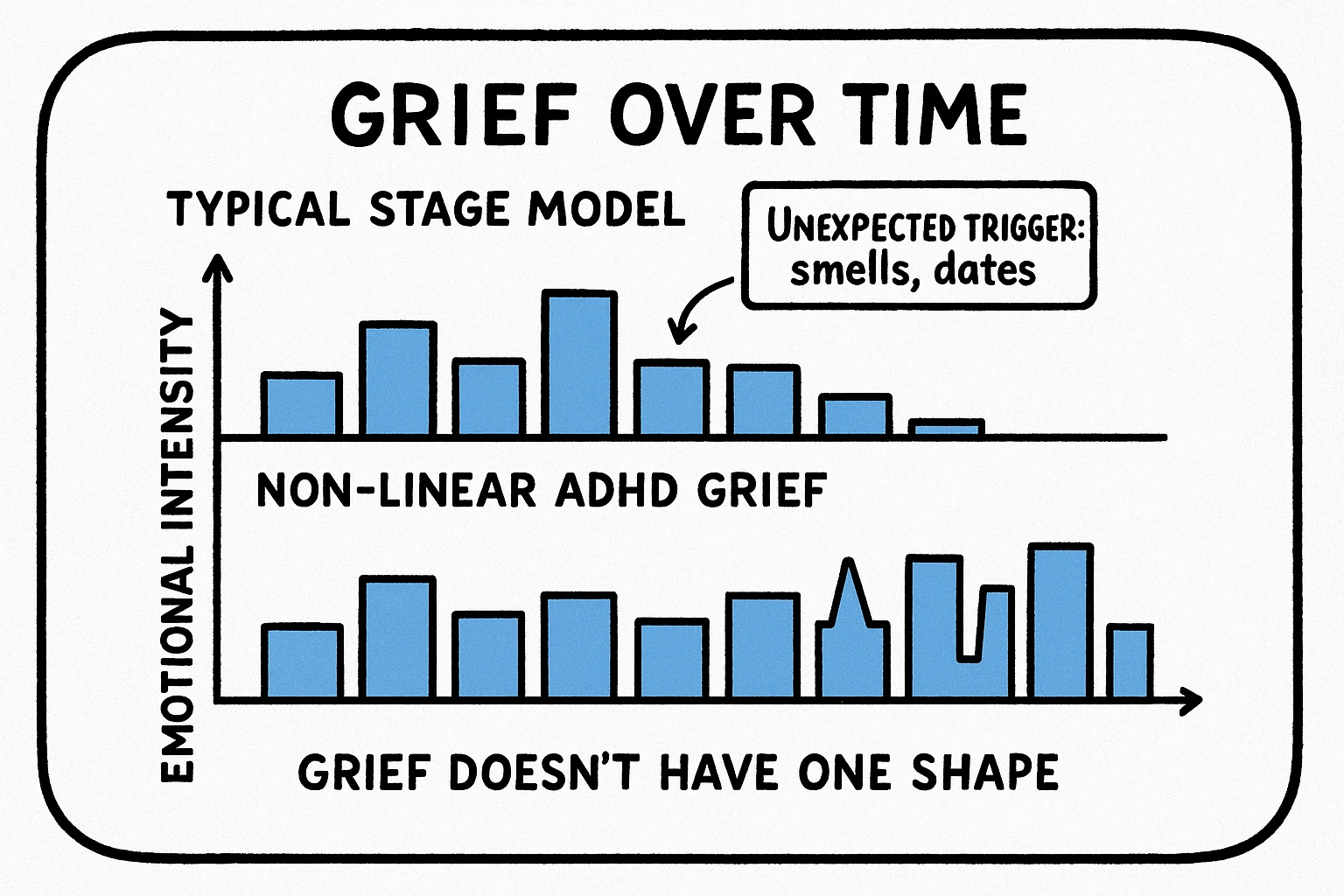

One of the most bewildering aspects of ADHD is time blindness—the difficulty perceiving and managing the passage of time. This particular challenge can radically transform the grieving process. For many with ADHD, grief doesn't progress neatly through stages. Instead, it often presents as a "jagged" and "fragmented" experience, where intense waves of emotion can resurface unexpectedly, long after conventional timelines suggest they should "pass."

You might find yourself feeling a profound pang of recent loss months or even years down the line, as if it just happened yesterday. This happens because your brain doesn’t always categorize and store emotional memories in a linear fashion, meaning the emotional intensity of the initial loss can remain readily accessible, triggered by various cues. This non-linear pattern means you might grieve in bursts, find yourself deeply absorbed in memories, or suddenly feel the full weight of your loss come crashing down at an unexpected moment. It’s not uncommon to feel ashamed or confused by this, but it's a perfectly normal expression of ADHD grief.

Executive Function Breakdown: Navigating Logistics in Crisis

When a loved one passes, there's often a deluge of practical tasks that require planning, organization, and follow-through—precisely the executive functions that ADHD makes challenging even on the best of days. During grief, this breakdown can feel catastrophic. Scheduling memorial services, managing paperwork, communicating with family, or even just maintaining a basic routine can become monumental tasks.

The brain fog and emotional overwhelm that often accompany grief amplify typical ADHD challenges, making it nearly impossible to prioritize, initiate, or complete necessary actions. This isn’t a lack of caring; it’s a temporary, yet debilitating, exacerbation of executive dysfunction. You might find yourself "hyperfocusing" on irrelevant details as a coping mechanism, or completely avoiding crucial ones. Understanding this pattern allows you to seek support not just for emotional healing, but for practical assistance, too.

Unique Forms of Grief for ADHD Individuals

Beyond the immediate loss of a loved one, individuals with ADHD often grapple with other, less recognized forms of grief that profoundly impact their emotional landscape.

The Grief of a Late Diagnosis: Mourning a Life Unlived

For many adults, an ADHD diagnosis comes later in life, after years of struggling without understanding why. This journey frequently involves ADHD and Rejection Sensitive Dysphoria (RSD) from misunderstood struggles. This "aha!" moment can bring immense relief and clarity, but it also often unleashes a potent, often overlooked, form of grief: mourning the life you could have lived.

This includes acknowledging missed opportunities, the burden of masking your symptoms to fit in, and the re-evaluation of past failures or regrets through a new lens. Psychological experts like those at Psychology Today highlight this "ADHD grief no one talks about"—the profound sadness over unfulfilled potential due to unrecognized neurodivergence. This grief is deeply personal and can be just as impactful as the loss of a person. It requires space for acknowledgment and a journey toward self-acceptance and reframing your past with compassion.

ADHD, Trauma, and Disenfranchised Grief: Emotions Not Understood

The intersection of ADHD and trauma is a significant consideration. Individuals with ADHD are at a higher risk for traumatic experiences, such as peer victimization or intimate partner violence. These experiences can lead to complex trauma (C-PTSD), which often mimics or exacerbates ADHD symptoms, making the diagnostic picture confusing. Research shows that adults with ADHD are nearly seven times more likely to have PTSD.

When grief strikes atop this landscape of past trauma, it can intensify emotional dysregulation, making processing even more difficult. Furthermore, ADHDers frequently experience disenfranchised grief—grief that isn't openly acknowledged, supported, or even understood by society. This can happen when people don't grasp the intensity of your reactions, the time blindness that makes grief non-linear, or even the unique grief over a late diagnosis. When your emotions aren't validated, it can lead to profound isolation and a sense that your pain is somehow "wrong" or excessive.

Neurodivergent-Friendly Paths to Healing & Support

While your experience of grief is unique, there are specific, practical approaches that align with the neurodivergent brain, fostering healing and self-compassion.

Self-Compassion & Releasing the Guilt: "You Are Not Broken"

Perhaps the most vital step in healing is to unburden yourself from guilt and shame. Your brain's unique response to grief is not a failing; it’s merely a different way of processing profound loss. Embrace the idea that it's okay to grieve differently. You are not broken because your grief doesn't look like someone else's.

Cultivating self-compassion involves acknowledging your pain without judgment, recognizing that imperfection is part of the human—and neurodivergent—experience, and treating yourself with the same kindness you would offer a struggling friend. Challenge any internalized narratives that tell you you're reacting "too much" or "not enough." Your feelings are valid, exactly as they are.

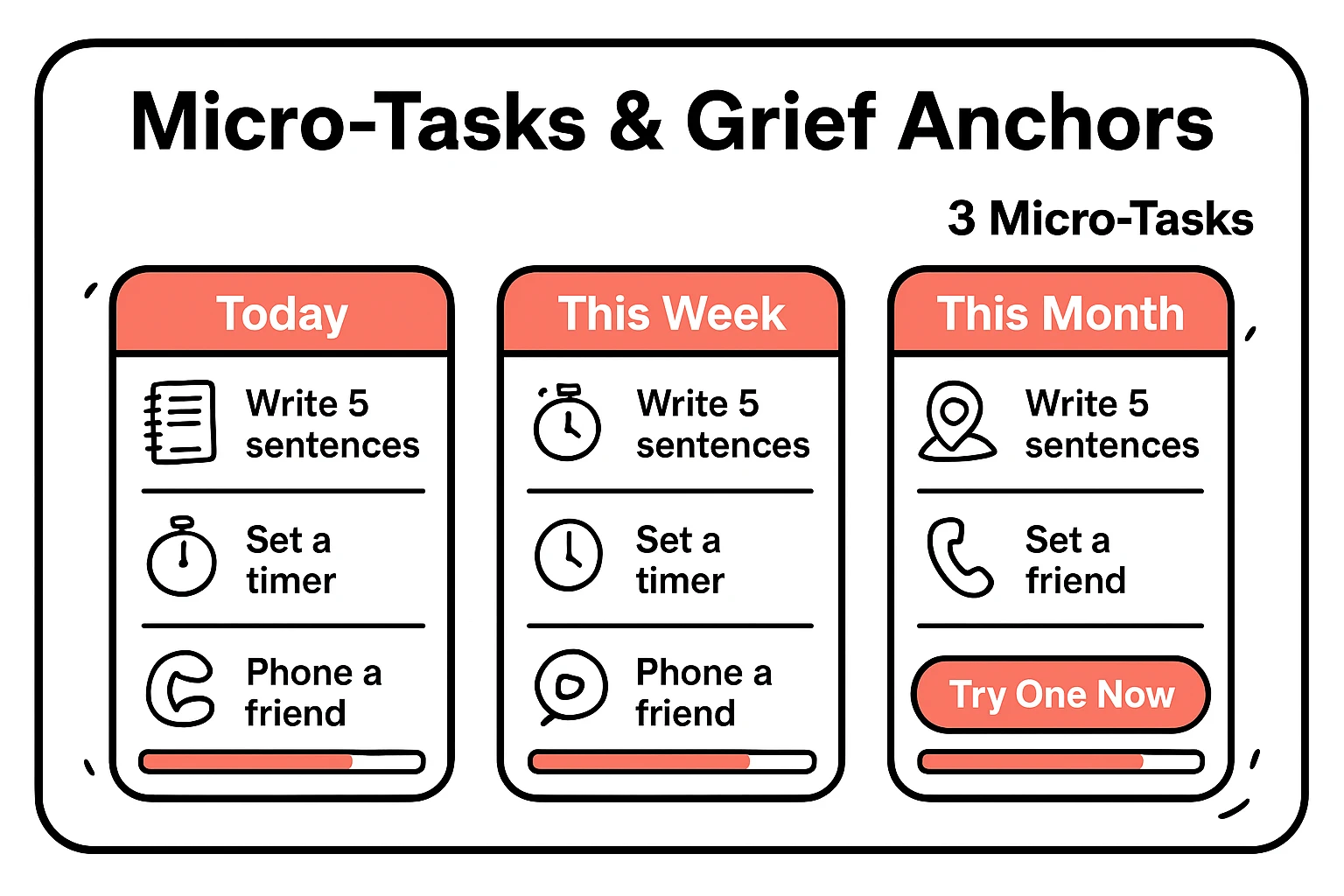

Practical Strategies for Emotional Regulation & Processing (Micro-Tasks & Grief Anchors)

Given the challenges with executive function and emotional overwhelm, traditional grief advice often falls flat. Instead, focus on strategies that respect your brain's natural tendencies:

- Grief Anchors: These are small, consistent actions or rituals that provide stability and a sense of connection during times of overwhelm. An anchor could be looking at a photo each morning, listening to a specific song, lighting a candle, or writing a short journal entry about your loved one. These aren't meant to "solve" your grief but to provide small, manageable points of focus and remembrance.

- Micro-Tasking Grief: Break down emotional processing into tiny, digestible steps. Instead of "process grief," try "think about my loved one for 5 minutes," "write one sentence that expresses how I feel," or "listen to one song that reminds me of them." This combats [[ADHD and Executive Dysfunction: Strategies for Boosting Productivity]] by making the emotional work feel achievable.

- Mindfulness Techniques: Methods like RAIN (Recognize, Allow, Investigate, Nurture) or FOUL (Feel, Observe, Understand, Let go) can be adapted to manage intense emotions. They involve observing your feelings without judgment, creating a small sense of distance, and reducing emotional reactivity.

- Visual Externalization: For a brain that thrives on visual cues, externalizing your grief can be powerful. This might involve creating a physical memory box, a digital collage, or a "grief journal" where you can literally see your thoughts and feelings. This helps combat memory issues and provides a tangible outlet for intense emotions.

Building a Neuro-Inclusive Support Network: Communicating Your Needs

Supporting someone with ADHD through grief requires a unique understanding. If you have ADHD, communicating your specific needs to neurotypical friends and family can be invaluable. Explain that your grief isn't linear, that you might seem fine one moment and overwhelmed the next, or that you might need practical help with tasks more than emotional conversations.

For allies, understanding that [[ADHD Coaching: Tailoring Strategies for the Neurodivergent Mind]] means accepting non-linear grief is key. Offer concrete, practical support: "Can I help with groceries?" instead of "Let me know if you need anything." Be patient when emotional regulation is challenging, and remember that sometimes, a familiar presence doing a quiet task nearby (body doubling) is more helpful than intense conversation.

Conclusion: Finding Your Non-Linear Path to Healing

Grieving with ADHD is a journey marked by intense emotions, non-linear processing, and unique challenges that often go unrecognized. But understanding your neurodivergent brain's impact on grief is incredibly empowering. It allows you to move beyond self-blame and embrace a path of healing that genuinely respects your internal experience.

Remember, healing isn't about following a prescribed timeline; it's about navigating your internal landscape with self-compassion, utilizing strategies that work for your brain, and building a supportive ecosystem that truly understands. Your feelings are valid, your process is authentic, and your capacity to heal, though unique, is profound. If you find yourself struggling to cope, remember that professional help tailored to neurodivergent needs.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Q1: Why does my grief feel so much more intense or overwhelming than what my neurotypical friends describe?

Your neurodivergent brain is wired differently, particularly in how it processes and regulates emotions. Research shows that emotional dysregulation is a common trait in ADHD, meaning your amygdala (emotion center) can react more intensely, and your prefrontal cortex (regulation center) might struggle to modulate those responses. This leads to heightened emotional experiences and difficulty controlling them, making grief feel incredibly overwhelming. It's a neurobiological difference, not a fault.

Q2: I feel like I'm grieving "wrong" because my emotions are inconsistent. Is this normal for ADHD?

Absolutely. This is a common experience stemming from ADHD's time blindness and non-linear emotional processing. Your grief won't follow a neat timeline or traditional "stages." Intense emotions can resurface days, months, or even years after a loss, feeling as fresh as the first day. This "jagged" and "fragmented" grieving process is perfectly normal for the ADHD brain and isn't a sign that you're grieving incorrectly.

Q3: How can I manage the practical tasks associated with loss (like paperwork, arrangements) when my executive functions are completely shut down

This is a significant challenge when ADHD meets grief. Your executive functions—like planning, organization, and initiation—are already difficult, and grief amplifies this. Prioritize ruthlessly: what must be done, and what can wait or be delegated? Leverage your support network for these specific tasks, asking for concrete help rather than general offers ("Could you help me sort medical bills for an hour?" instead of "Can you help?"). Breaking down tasks into micro-steps can also help, e.g., "Open one envelope" instead of "Do all the paperwork."

Q4: I received my ADHD diagnosis after a major loss, and now I'm grieving both the person and a life I feel I "lost" due to undiagnosed ADHD. Is this common?

Yes, this is a powerful and often overlooked form of grief, sometimes called "the grief of a late diagnosis." Psychology Today highlights this profound sadness over missed opportunities, unfulfilled potential, and the burden of masking stemming from years of unrecognized ADHD. It's a valid and deeply personal grief that deserves acknowledgment and processing alongside your other losses.

Q5: What are "grief anchors" and how can they help an ADHD brain?

Grief anchors are small, consistent actions, rituals, or objects that provide stability, connection, and a gentle structure during the chaotic experience of grief. For an ADHD brain, they counteract overwhelm by creating manageable, predictable points of remembrance. This could be looking at a specific photo, lighting a candle, listening to a particular song, or writing a single sentence in a journal each day. They are not about "fixing" grief, but about providing small, achievable ways to engage with it without executive function overload.