You've probably felt it – that swirling chaos, the brilliant idea that slips away, the deadline that looms large but feels impossibly far. Is it just everyday forgetfulness, or something more fundamental about how your brain works? As you evaluate your experiences and seek to understand the deeper impact of ADHD, you're not just looking for a diagnosis; you're looking for answers to the "why" behind your daily challenges.

For many with ADHD, the core explanation lies in executive functions. These aren't just minor quirks; they're the brain's command center, orchestrating everything from planning your day to managing your emotions. While most resources might scratch the surface, we're diving deep into the fascinating, sometimes frustrating, world of how ADHD uniquely interacts with these critical cognitive processes. Our goal is to equip you with authoritative, research-backed insights and practical strategies, transforming confusion into confident clarity.

The Executive Suite: A Deep Dive into Key Cognitive Processes Affected by ADHD

Executive functions are a set of mental skills that include working memory, flexible thinking, and self-control. They're what help us manage ourselves and our resources to achieve goals. In the ADHD brain, this "executive suite" often operates differently, leading to widespread impacts on daily life. About 40-60% of adults with ADHD experience substantial challenges in executive functions, profoundly influencing their personal and professional worlds. To truly understand, we need to break down each component.

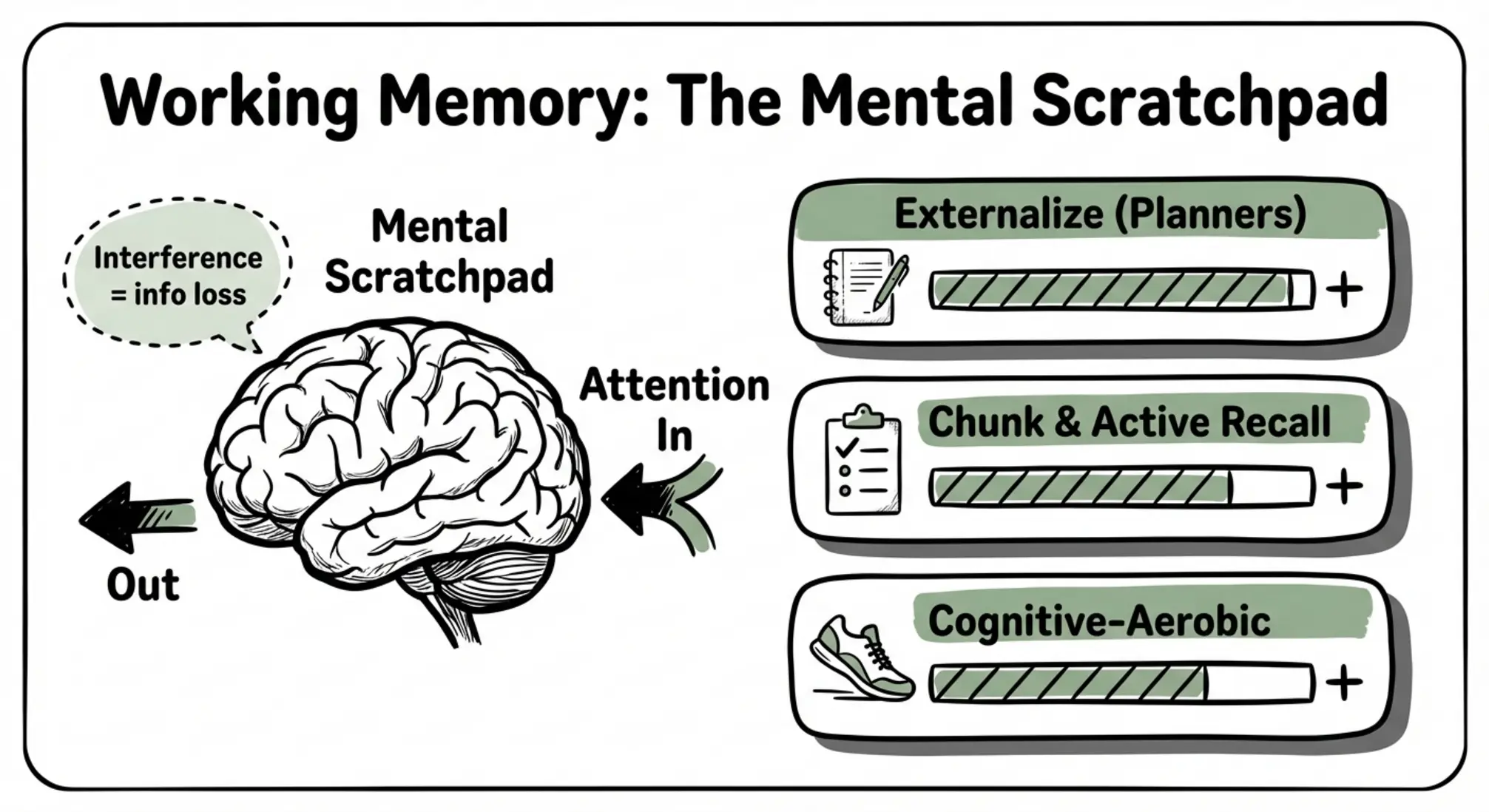

Understanding Working Memory Deficits: The "Mental Scratchpad" Conundrum

Think of working memory as your brain's temporary notepad, where you hold and manipulate information. It’s crucial for everything from remembering a phone number you just heard to following multi-step instructions. For many with ADHD, this mental scratchpad is notoriously unreliable. Why is my memory so bad with ADHD, you might wonder? It's not necessarily about long-term storage, but about information constantly getting "kicked out."

This isn't just about general forgetfulness. Research suggests that attention interference plays a significant role. If your attention shifts, even momentarily, the information in your working memory can be lost. This explains why you might forget what you were going to say mid-sentence, or lose your keys despite just holding them. Approximately 75-85% of youth with ADHD show deficits in working memory, a challenge that often persists into adulthood.

To manage memory recall issues with ADHD, externalization is key. Don't rely solely on your internal notepad. Utilize digital planners, physical notebooks, and voice memos. Chunking information into smaller, digestible parts can also aid retention, as can active recall techniques where you deliberately try to remember information. Emerging research also highlights the role of physical activity, especially cognitive-aerobic exercise, in improving working memory in children with ADHD, offering a promising avenue for adults as well.

Inhibition & Impulsivity: More Than Just Hyperactivity

Inhibition is the ability to stop an automatic response or an urge. It's what allows you to pause before speaking, resist distraction, or delay gratification. Impulsivity, often seen as a hallmark of ADHD, is a direct result of impaired inhibitory control. But it's far more nuanced than simply being "hyper." About 21-46% of individuals with ADHD struggle with inhibitory control.

Impulsivity can manifest as:

- Motor Impulsivity: Fidgeting, restlessness, sudden movements.

- Verbal Impulsivity: Interrupting others, speaking without thinking, blurting out answers.

- Cognitive Impulsivity: Jumping to conclusions, acting without considering consequences, making rash decisions.

Psychologist Dr. Russell Barkley proposed the "30% executive function delay rule," suggesting that individuals with ADHD typically function at about 30% below their chronological age in terms of executive control. This isn't a deficit of intelligence but a developmental delay in the cognitive mechanisms that regulate behavior. This understanding fosters self-compassion, recognizing that overcoming planning issues with ADHD isn't a matter of willpower alone.

To "tame" impulsivity, strategies like the "24-hour rule" for major decisions, pre-commitment strategies (e.g., leaving credit cards at home for impulse purchases), and mindfulness practices to create a pause before reacting can be highly effective.

Planning & Organization Challenges: The "Now" vs. "Not Now" Brain

Planning is the ability to set goals and devise steps to achieve them. Organization involves arranging tasks and materials systematically. For many with ADHD, starting tasks and prioritizing can feel like navigating a dense fog. This is often linked to "time blindness," where the future feels distant and abstract, making long-term planning incredibly difficult. The "now" vs. "not now" brain struggles to connect current actions with future consequences.

One of the significant contributors to planning issues with ADHD is the "future self disconnect." When planning for tomorrow, it often feels like you're planning for a hypothetical person, not your actual self who will face those tasks. This makes it hard to allocate resources or anticipate obstacles.

Effective strategies for life planning with ADHD involve externalizing your plans, breaking down large tasks into smaller, manageable steps, and using visual cues. Backward planning (starting from the deadline and working backward) can make the future feel more concrete. The "just 10 minutes" rule (or 20 minutes for some), where you commit to working on a task for a short, finite period, can help overcome initiation paralysis. Body doubling—working alongside someone else, even virtually—can also provide an external push for task initiation and focus.

Emotional Regulation in ADHD: The Unseen Struggle

Emotional dysregulation (ED) refers to difficulty managing the intensity and duration of emotional responses. It's a significant, yet often overlooked, aspect of ADHD, affecting an estimated 34-70% of adults with ADHD and about half of children. This isn't just about moodiness; it stems from impaired top-down executive control, directly impacting the frontal-limbic circuit—the part of the brain responsible for processing emotions.

Adults with ADHD are more likely to use maladaptive emotion regulation strategies, such as avoidance or rumination. This can lead to increased irritability, quick temper, anxiety, and profound frustration. A specific and particularly painful manifestation is Rejection Sensitive Dysphoria (RSD), an extreme emotional sensitivity and pain triggered by the perception (real or imagined) of rejection, criticism, or failure. RSD can be debilitating, causing individuals to avoid situations where they might face criticism, leading to isolation.

The science behind this involves a nervous system that can be hyper-reactive, meaning minor annoyances can trigger an intense "fight or flight" response. Understanding these emotional dynamics is crucial for self-compassion and effective coping.

Strategies for navigating emotional storms include principles from Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) and Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT), which focus on identifying triggers, challenging unhelpful thought patterns, and developing distress tolerance skills. Breathwork, creating "decompression spaces," and the act of externalizing your feelings by journaling or talking to a trusted person can also be invaluable.

The Silent Symptoms: Cognitive Manifestations Often Overlooked

While working memory, inhibition, and planning get significant attention, there are other cognitive symptoms of ADHD that are frequently ignored, even though they represent the subtle, yet deeply impactful, internal experience of living with ADHD:

- Internal Thought Variability: This isn't just a busy mind; it's the experience of constant shifting, fleeting thoughts, and multiple simultaneous thought streams that can make sustained internal focus challenging. It's like having a dozen browser tabs open in your mind, all demanding attention.

- Processing Speed Variability: Individuals with ADHD don't necessarily have slow processing speed across the board, but rather, their processing speed can be inconsistent. There are times of lightning-fast insights, and times where basic information feels stuck in molasses.

- "Brain Crash" / Cognitive Overwhelm: This is the feeling of sudden mental shutdown after intense focus or prolonged cognitive effort. It's not just fatigue; it's a profound inability to process further information, often leading to a need for complete mental disengagement.

These internal experiences are rarely discussed in mainstream ADHD resources, yet they are profoundly validating for those who live them. Acknowledging these nuances can bridge the gap for those who feel their ADHD experience doesn't quite fit the typical descriptions of trouble focusing but not ADHD.

Bridging the Gap: Tailored Strategies for Each Cognitive Challenge

Understanding the "why" is the first step; the next is applying the "how." Here are practical, research-informed strategies to support your unique cognitive landscape:

- Working Memory Boosters:

- Externalize Everything: Use planners, calendars, note-taking apps, and even physical objects as external memory aids. Don't fight your brain; augment it.

- Monotasking: Focus on one task at a time. Close irrelevant tabs, put your phone away, and dedicate your full, albeit brief, attention.

- Chunking: Break down information into smaller, more manageable units. Instead of a 10-step process, focus on 2 steps at a time.

- Active Recall: Instead of just re-reading, actively try to recall information from memory. This strengthens the memory trace.

- Cognitive-Aerobic Exercise: Incorporate physical activity that also engages your brain (e.g., dance, martial arts, sports with strategy).

- Taming Impulsivity:

- The 24-Hour Rule: For significant decisions (purchases, commitments, emotional responses), implement a mandatory waiting period. This provides crucial time for the prefrontal cortex to catch up.

- Pre-Commitment Strategies: Structure your environment to make impulsive choices harder (e.g., unhealthy snacks out of sight, blocking distracting websites during work).

- Mindfulness for Pausing: Practice short mindfulness exercises to increase your awareness of urges and create a momentary gap before acting on them.

- Mastering Planning & Organization:

- Backward Planning: Start with your desired outcome or deadline and work backward, mapping out each step.

- Visual Cues: Use whiteboards, sticky notes, and visual timers. Seeing your tasks can make them more "real."

- "Just 10 Minutes" (or 20): Commit to working on a dreaded task for a very short, specified period. Often, the act of starting is the hardest part.

- Flexible Routines: Instead of rigid schedules, create flexible routines that accommodate your natural energy fluctuations.

- Body Doubling: Work on tasks in the presence of another person (in-person or virtually). Their presence can provide an external structure that aids focus.

- Navigating Emotional Storms:

- Identify Triggers: Keep an emotion journal to track what precedes intense emotional reactions.

- "DEAR MAN" Skills (DBT-inspired): When communicating difficult emotions, practice describing, expressing, asserting, and reinforcing while remaining mindful, appearing confident, and negotiating.

- Breathwork Techniques: Simple deep breathing exercises can quickly calm your nervous system.

- Decompression Spaces: Identify physical or mental spaces where you can retreat when feeling overwhelmed to regulate your emotions.

- Harnessing Hyperfocus:

- Strategic Allocation: Intentionally direct your hyperfocus towards productive tasks.

- Timeboxing: Set a timer for hyperfocused tasks to ensure you don't lose track of other responsibilities.

- Environmental Cues: Create specific environments that signal "hyperfocus mode" (e.g., certain music, specific workspace).

Next Steps: Moving From Insight to Action

Understanding the intricate ways ADHD impacts executive functions offers immense validation and empowerment. It shifts the blame from character flaws to neurological differences, paving the way for targeted strategies and self-compassion. This detailed breakdown of cognitive symptoms of ADHD, from working memory to emotional dysregulation, is designed to give you the clarity you need to move forward.

If you're seeking to understand the unique "mental internet" that is your ADHD brain more deeply, or explore which executive functions are most impacting your daily life, we're here to guide you.

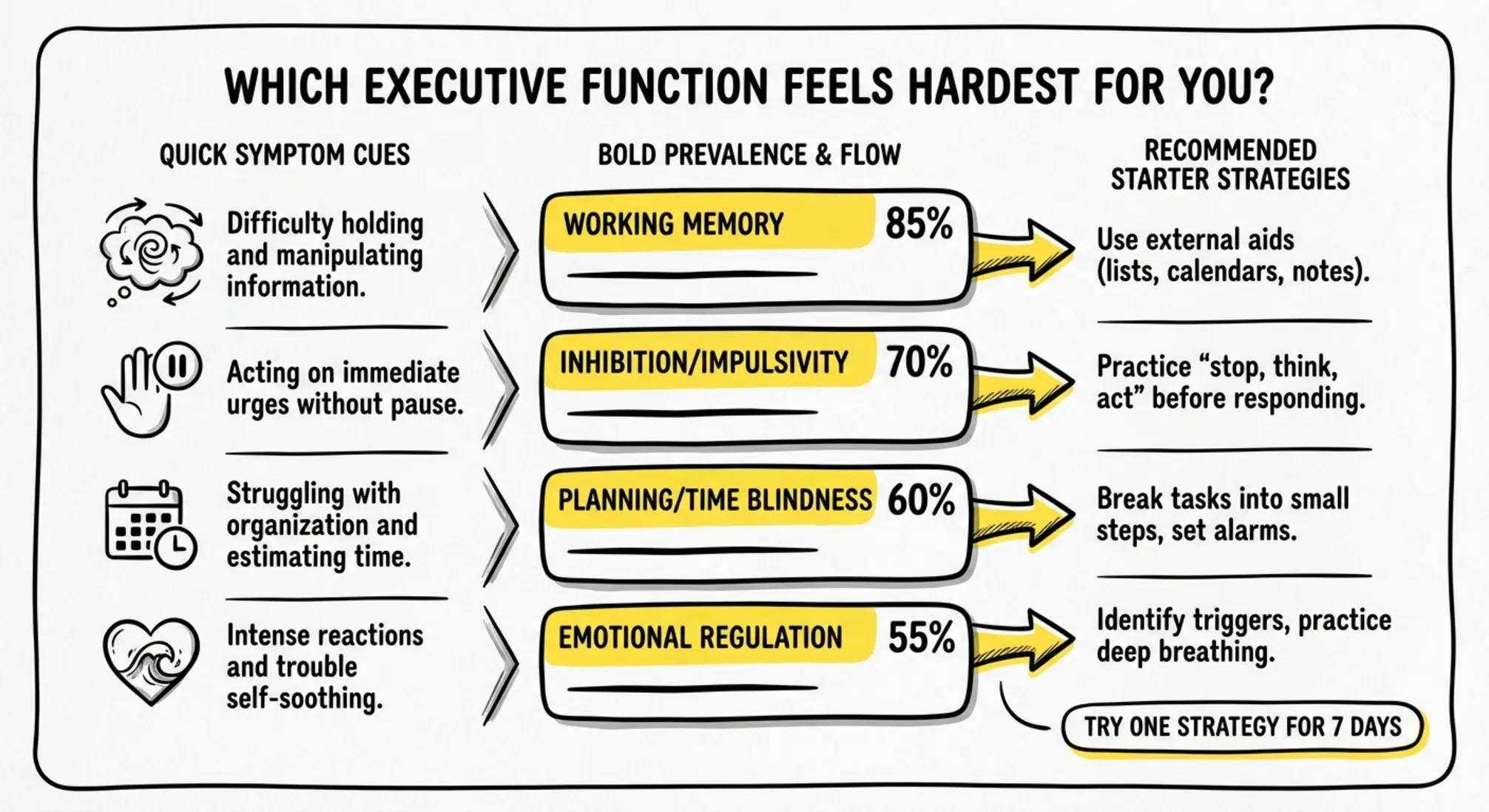

What's Your Biggest Executive Function Roadblock? A Quick Self-Assessment

Based on what we've discussed, which of these areas resonates most with your daily struggles? Pinpointing your primary challenge can help you prioritize where to focus your energy and what strategies to try first.

- "I often lose track of what I'm doing mid-task, forget instructions, or misplace items." (Focus: Working Memory)

- "I struggle to stop myself from interrupting, making impulsive purchases, or acting without thinking." (Focus: Inhibition/Impulsivity)

- "Starting tasks feels impossible, I can't seem to prioritize, and deadlines always catch me off guard." (Focus: Planning & Organization)

- "My emotions feel too big, I react intensely to perceived criticism, or I get overwhelmed easily." (Focus: Emotional Regulation)

- "My mind is constantly racing with multiple thoughts, or I hit a wall and can't process anything more." (Focus: Overlooked Cognitive Symptoms)

Acknowledge your challenge, pick one strategy from the relevant section, and commit to trying it for one week. Small, consistent steps build powerful momentum.

Frequently Asked Questions about ADHD and Executive Functions

Q: Is executive dysfunction the same as ADHD?

Executive dysfunction is a core component of ADHD, but they are not identical. ADHD is a neurodevelopmental disorder characterized by persistent patterns of inattention and/or hyperactivity-impulsivity. Executive dysfunction refers specifically to the difficulties with the brain's "managerial" functions, which are significantly impacted in ADHD. Approximately 89% of youth with ADHD show deficits in at least one executive function.

Q: Can executive function deficits improve in adults with ADHD?

Yes, with targeted strategies, therapy, coaching, and sometimes medication, adults can significantly improve their executive function skills. While the underlying neurological differences remain, the brain is highly adaptable, and new pathways and coping mechanisms can be developed. Consistent application of strategies, much like building a muscle, strengthens these areas.

Q: How does emotional dysregulation differ from mood disorders in ADHD?

Emotional dysregulation (ED) in ADHD is characterized by intense, rapid emotional responses that are difficult to manage, often tied to challenges in the brain's frontal-limbic circuit. While it can mimic aspects of mood disorders like Bipolar Disorder or Borderline Personality Disorder, ED in ADHD is primarily linked to impaired executive control over emotional responses, rather than a primary mood disturbance. It's crucial to differentiate these for accurate treatment.

Q: Why do I struggle with time blindness even when I try to plan?

Time blindness is a pervasive issue for many with ADHD, where time feels ambiguous and often perceived as "now" or "not now." This is largely due to challenges in working memory and the brain's ability to accurately estimate and track the passage of time. Planning for a future event often feels like planning for a hypothetical "future self" rather than your present self, making it less motivating and harder to engage with. Externalizing time with visual timers and breaking tasks into very small, defined segments can help bridge this gap.

Q: Are there any emerging treatments or approaches for executive dysfunction in ADHD?

Beyond traditional medication and behavioral therapies, there's growing interest in interventions like cognitive training (though results can be mixed), mindfulness practices, and lifestyle modifications. For instance, meta-analyses suggest that physical activity, particularly cognitive-aerobic exercise, shows promise in improving working memory in those with ADHD. Researchers are also exploring novel neurofeedback techniques and the use of technology to support executive function externally. These are not cures, but complementary approaches to improve the life planning of those with ADHD.