The ADHD-Emotion Connection: How Brain Differences Impact Feelings

Ever felt like your emotions have a mind of their own? That a tiny spark can ignite a wildfire of feelings, or that staying upset feels like being stuck in quicksand? If you live with ADHD, these intense emotional experiences are not just "part of your personality" or a "flaw you need to fix." They are deeply rooted in the unique way your brain is wired—a wiring that, while chaotic at times, is also endlessly fascinating.

You're likely here because you're searching for answers, trying to understand why your emotional landscape can be so turbulent. Perhaps you're feeling overwhelmed, or wondering if what you experience is "normal" for ADHD, or even questioning if it's something more. What you need isn't just surface-level advice; it's a deep dive into the "why" and "how," a scientific explanation blended with empathetic understanding.

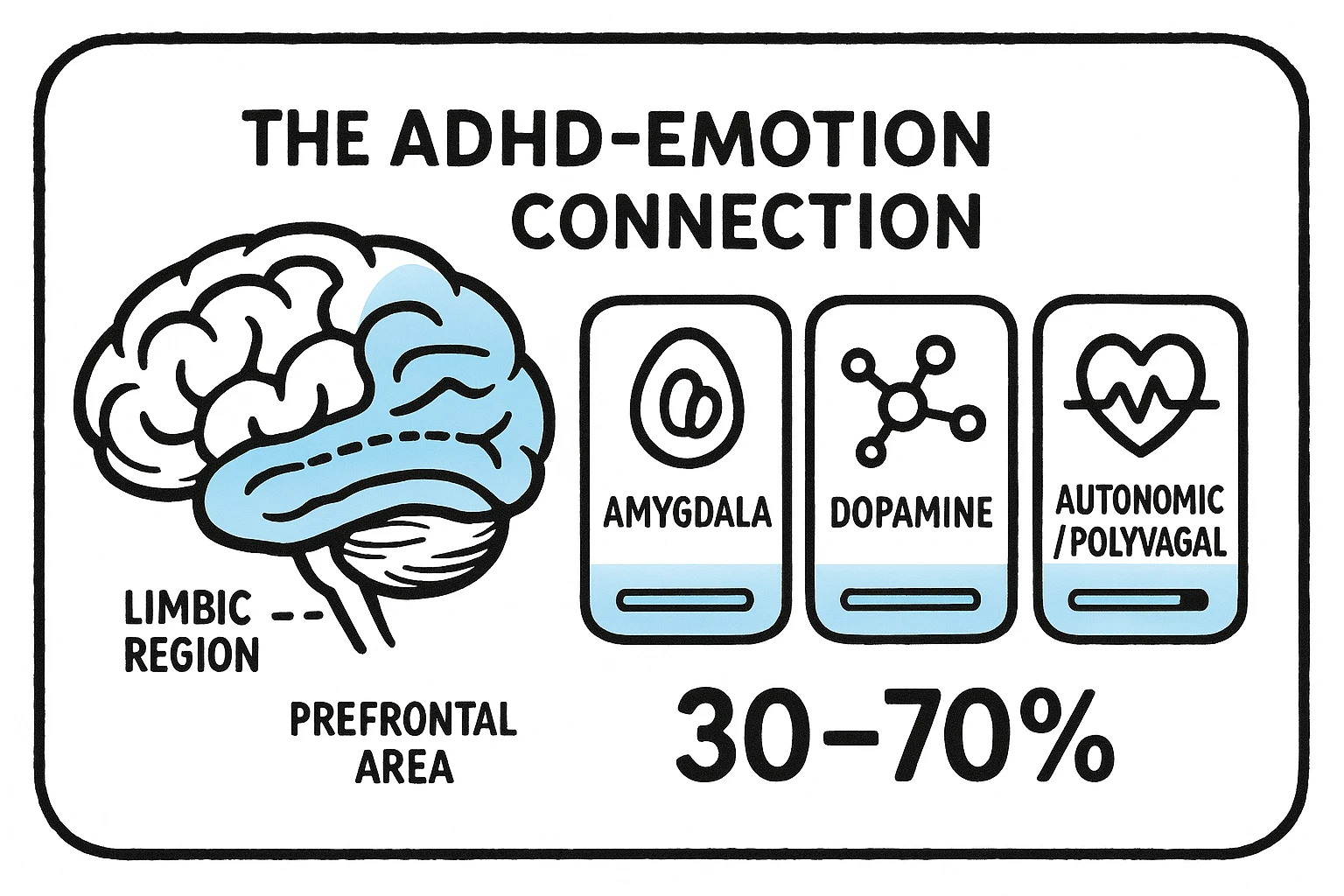

You're not alone. Emotional dysregulation affects a significant portion of adults with ADHD, with some estimates ranging from 30% to 70%, and even as high as 72-73% in certain studies. This isn't a minor footnote; it's a central experience that impacts relationships, work, and overall quality of life.

Here, we'll strip away the judgment and explore the neurological underpinnings of emotional intensity in ADHD. We'll bridge the gap between scientific understanding and the lived experience, helping you understand not just what you feel, but why your brain processes emotions in this beautifully chaotic way.

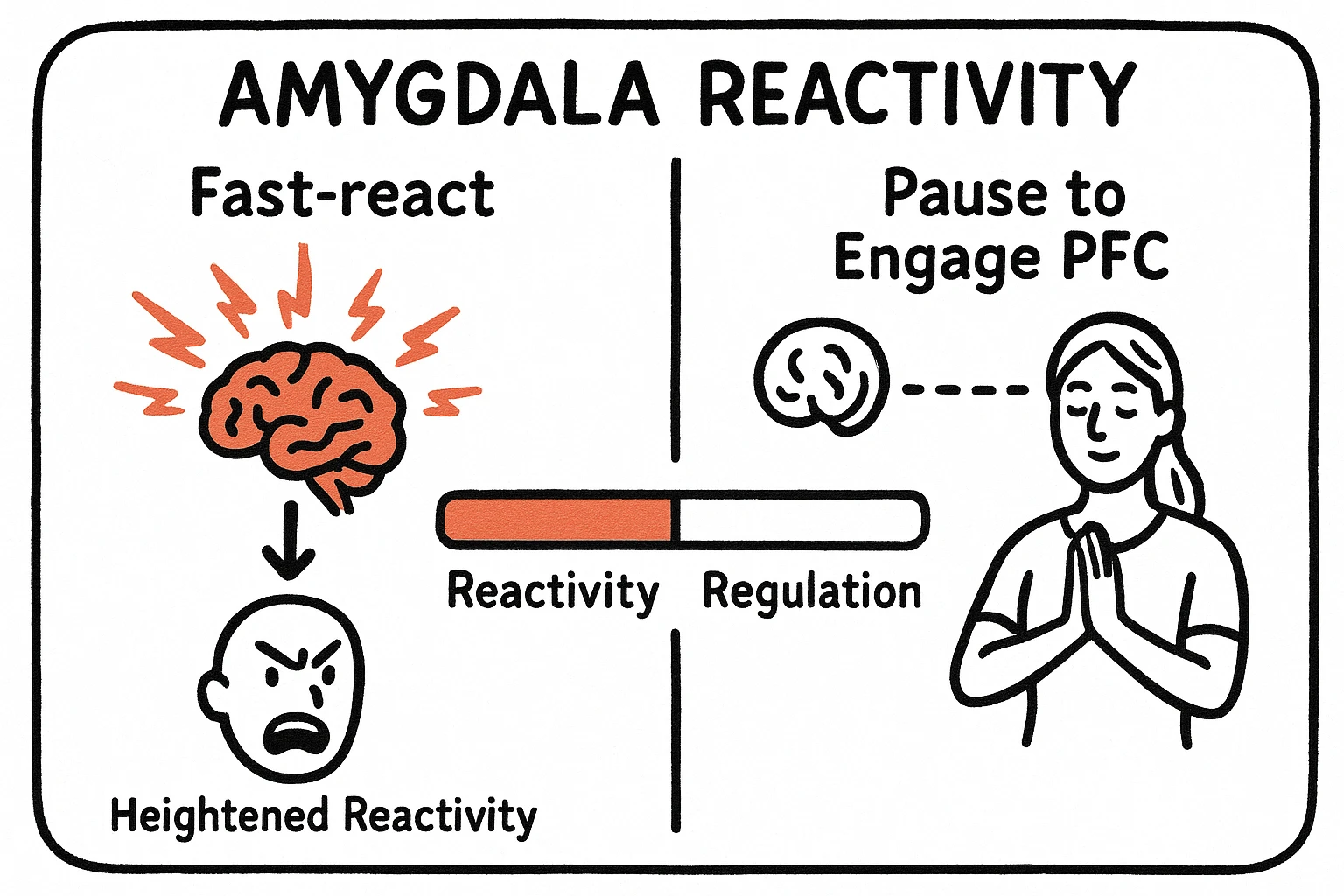

The Amygdala and ADHD: Understanding Emotional Reactivity

Imagine your brain's emotional smoke detector. That's largely your amygdala, a small, almond-shaped region deep within your temporal lobe. In an ADHD brain, this smoke detector often seems extra sensitive, sometimes even without proper calibration. This means it's quicker to sense a threat or emotional trigger, and quicker to sound the alarm.

Research shows that dysfunction in brain networks involving the amygdala and orbitofrontal cortex (part of your prefrontal cortex, which we'll get to later) is a key factor in emotional dysregulation. Your amygdala may be overactive, processing emotions with intense gusto, while the brain regions meant to modulate that intensity might be underactive.

Think about it: a small annoyance that might cause a neurotypical person a momentary frown could trigger an intense wave of frustration or even rage for someone with ADHD. This isn't a failure of willpower; it’s your brain’s rapid-response emotional system working overtime. Your amygdala is firing, leading to what feels like an immediate, overwhelming emotional response, often before your rational brain has a chance to catch up.

This heightened reactivity contributes to experiences like Rejection Sensitive Dysphoria (RSD), where perceived criticism or rejection feels disproportionately painful, or to rapid emotional outbursts that feel out of character. It's why small things feel like big deals—because your brain's alarm system is genuinely reacting to them that way.

So, what can we do when the amygdala calls all the shots? Strategies like grounding techniques (engaging your senses to pull you into the present), or practicing a "pause" before responding, are brain-informed ways to engage your prefrontal cortex and create a tiny window for rational thought before the emotional flood takes over.

For a deeper dive into understanding and managing these rapid emotional shifts, explore our resource on [The Amygdala and ADHD: Understanding Emotional Reactivity]().

Dopamine's Role in ADHD Mood Swings

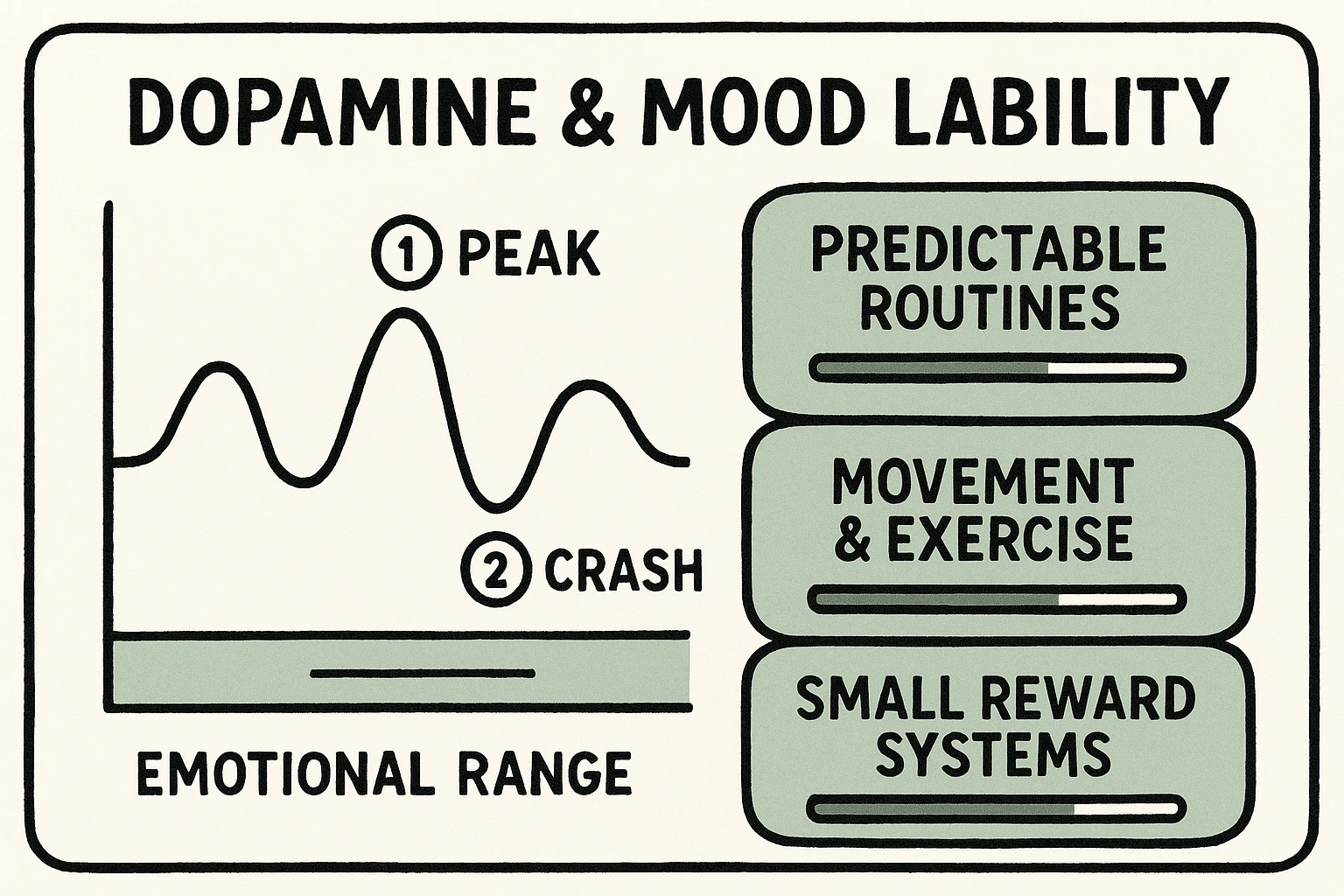

Have you ever experienced emotional "crashes" or sudden shifts in mood that seem to come out of nowhere? You might be riding the dopamine rollercoaster. Dopamine, a key neurotransmitter, is crucial for motivation, reward, pleasure, and—you guessed it—emotional regulation. In ADHD, the brain affects how it regulates dopamine, which can lead to a less effective "brake" on emotional reactions.

Think of dopamine like the fuel in your car's engine. Too little, and you feel sluggish, unmotivated, and perhaps irritable. Too much, and you might feel overstimulated or impulsively chase the next rewarding sensation. For someone with ADHD, this "fuel system" often struggles to maintain a steady level. Your brain might experience a rapid depletion of dopamine after an exciting or hyper-focused activity, leading directly to a mood crash or a feeling of anhedonia (inability to experience pleasure).

This dysregulation contributes to mood lability—the tendency for moods to swing quickly and intensely. One moment you're highly engaged, energized by a task you find stimulating, and the next you can feel deflated, irritable, or even overwhelmed by trivial matters. This "all or nothing" emotional experience is a common hallmark of dopamine dysregulation.

Understanding this mechanism helps explain why predictable routines, regular exercise, and a balanced diet aren't just good general advice—they're specific, brain-informed strategies that can help stabilize your dopamine levels and reduce the intensity of mood swings. They offer a more consistent "drip" of dopamine rather than relying on sporadic "bursts" that lead to subsequent crashes.

To learn more about how to navigate these fluctuating emotional states, delve into our guide on [Dopamine's Role in ADHD Mood Swings]().

Executive Functions and Emotional Control: The Missing Link

Beyond the direct impact of the amygdala and dopamine, there's another powerful force at play: your executive functions. These are the "CEO" skills of your brain, residing primarily in your prefrontal cortex. They include abilities like:

- Inhibition: Your ability to stop and think before acting or speaking.

- Working Memory: Holding information in your mind to use for a task.

- Planning & Prioritization: Organizing tasks and foreseeing consequences.

- Self-Monitoring: Observing your own behavior and adjusting as needed.

In ADHD, executive function deficits impact your ability to control emotions. Dr. Russell Barkley, a leading expert on ADHD, emphasizes that emotional dysregulation is a core aspect of executive dysfunction. When these "CEO" skills are impaired, it's harder to:

- Filter emotional responses: You might blurt out an angry comment before thinking, or react impulsively to a perceived slight.

- Process complex emotions: Understanding nuance in your own feelings or those of others can be a struggle, leading to misinterpretations or feeling "stuck" in an emotional state.

- Regulate your emotional expression: Shifting from one emotion to another, or containing an intense feeling appropriately, becomes more challenging.

Essentially, your emotional "thinking brain" (the prefrontal cortex) has trouble stepping in to regulate your emotional "feeling brain" (the amygdala). This weakened connection, where amygdala-prefrontal cortex communication is compromised, is a significant part of the picture. The feeling part of the brain often takes over the thinking part.

For example, if you have difficulty with working memory, you might struggle to recall past instances where you successfully managed a similar emotional challenge, leaving you feeling overwhelmed and without a strategy. If inhibition is weak, you might lash out in anger or burst into tears before you've fully processed what's happening.

Brain-informed coping strategies here focus on externalizing internal regulation. This could mean using journaling to process feelings (externalizing working memory), setting up clear "if-then" rules for emotional responses (externalizing planning), or having a trusted friend provide feedback (externalizing self-monitoring). These approaches provide scaffolding for your challenged executive functions, helping you regain a sense of mastery over your emotions.

To gain a deeper understanding of this crucial connection, explore our in-depth article on [Executive Functions and Emotional Control: The Missing Link]().

Polyvagal Theory Through an ADHD Lens: Regulating the Nervous System

Beyond specific brain regions and neurotransmitters, there's a broader system at play in your emotional life: your autonomic nervous system (ANS). The Polyvagal Theory, developed by Dr. Stephen Porges, provides a powerful framework for understanding how our nervous system shapes our emotional and behavioral responses, especially for those with ADHD.

Simply put, Polyvagal Theory describes three main states of your nervous system, each influencing how you perceive safety and respond to the world:

- Ventral Vagal (Safe & Social): This is your ideal state—calm, connected, curious. You can engage with others, think clearly, and regulate emotions.

- Sympathetic (Fight or Flight): When you perceive danger, your body mobilizes. You feel anxious, irritable, restless, or impulsive. This is crucial for survival but exhausting when prolonged.

- Dorsal Vagal (Freeze or Collapse): If fight/flight isn't possible, your system shuts down. You might feel numb, fatigued, dissociated, or utterly overwhelmed.

For someone with ADHD, your "neuroception"—your nervous system's unconscious assessment of safety or threat—is often biased. You might be more prone to interpreting neutral cues as threatening, leading to frequent or prolonged activation of sympathetic (fight/flight) or dorsal vagal (freeze/collapse) states, even in non-threatening contexts. This explains why you might feel keyed up, anxious, or overwhelmed by everyday tasks, or suddenly "shut down" when faced with too many demands.

The ADHD brain often has impaired autonomic flexibility. This means it's harder to smoothly shift between these states—to "calm down" after being activated, or to "snap out of it" after feeling overwhelmed. Studies on children with ADHD, for example, show altered parasympathetic mechanisms involved in emotion regulation, suggesting a difficulty in flexibly adapting the nervous system’s response.

Brain-informed strategies drawing from Polyvagal Theory focus on "vagal toning" and consciously promoting ventral vagal states. Simple practices like deep, slow breathing, humming, singing, or gargling can stimulate your vagus nerve and help shift your nervous system towards a calmer, more regulated state. Engaging in safe social interactions, listening to rhythmic music, or engaging in gentle movement can also help your nervous system feel safe and shift out of defensive states.

To explore this fascinating framework further and learn practical techniques for nervous system regulation, read our comprehensive article on [Polyvagal Theory Through an ADHD Lens: Regulating the Nervous System]().

Unpacking the Overwhelm: Differentiating & Co-occurring Conditions

It's natural to wonder if your intense emotional experiences are solely due to ADHD, or if something else is at play. The symptoms of ADHD emotional dysregulation can sometimes look similar to other conditions, leading to confusion and misdiagnosis. It’s important to understand the distinctions to ensure you receive the most effective support.

Many people with ADHD also experience co-occurring conditions like anxiety, depression, or an anxiety disorder. The constant internal chaos and external struggles often contribute to these mental health challenges. However, emotional dysregulation in ADHD typically manifests as rapid, intense, and often disproportionate reactions to triggers, with a relatively quick recovery once the trigger is removed or the highly stimulating activity ends. This differs from the sustained low mood of depression or the persistent worry of generalized anxiety.

Sometimes, ADHD emotional lability gets mistaken for conditions like Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD) or Bipolar Disorder. Here’s a quick overview of key distinguishing factors:

- Bipolar Disorder: Characterized by distinct, prolonged episodes of mania/hypomania and depression, lasting weeks or months. Mood instability in ADHD is generally more rapid and reactive to immediate circumstances, without the cycling of distinct manic/depressive episodes.

- Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD): Involves chronic (long-term) patterns of unstable relationships, self-image, and identity, along with intense fear of abandonment. While both ADHD and BPD can have emotional intensity and impulsivity, BPD includes a broader pattern of personality instability that isn't typically central to ADHD.

The key is always to work with a qualified mental health professional who can conduct a thorough assessment, differentiate symptoms, and provide an accurate diagnosis. Understanding the underlying mechanisms of your emotional responses, as we've explored here, can significantly aid this process and help your clinician tailor the most appropriate treatment plan.

Living with the ADHD-Emotion Connection: Practical Strategies & Support

Understanding the neurological roots of your emotional experiences is the first, crucial step. It provides validation and helps reduce self-blame. The next step is to translate this knowledge into practical strategies that help you manage your emotional landscape more effectively.

Here are some brain-informed approaches, synthesizing insights from across the ADHD-emotion connection:

- Identify Your Triggers (The Amygdala's Alarms): Pay attention to what reliably sets off intense emotional responses. Is it unexpected change, perceived criticism, sensory overload, or interpersonal friction? Once identified, you can create strategies to minimize exposure or prepare your brain's prefrontal cortex to step in more effectively.

- Stabilize Your Dopamine (Routine & Reward): Consistent sleep, regular meals, and planned physical activity help stabilize dopamine levels, reducing the intensity and frequency of mood swings. Incorporate small, predictable rewards throughout your day to provide a steady "drip" of positive reinforcement.

- Externalize Executive Functions: Don't rely solely on your internal executive skills. Use external aids:

- Journaling: Write down intense feelings to process them outside your head.

- "If-Then" Plans: Before entering a potentially triggering situation, decide beforehand: "IF X happens, THEN I will do Y."

- Visual Reminders: Place notes or cues in your environment to prompt regulated responses.

- Accountability Partners: A trusted friend or coach can help you monitor and reflect on emotional patterns.

- Tone Your Vagal Nerve (Nervous System Regulation): Incorporate daily practices that activate your ventral vagal system:

- Deep, diaphragmatic breathing: Slow, controlled breaths signal safety to your nervous system.

- Rhythmic activities: Walking, dancing, drumming, or listening to music can be very calming and regulating.

- Mindful movement: Yoga, tai chi, or gentle stretching.

- Safe Social Connection: Spend time with people who make you feel understood and calm.

- Build Self-Compassion: Recognize that your intense emotions are a product of your brain's unique wiring, not a moral failing. Cultivate a kind and understanding inner voice.

Seeking professional help is also a powerful act of self-care. Therapies like Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) and Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT) can teach valuable emotion regulation skills. An ADHD coach can help you apply brain-informed strategies to your daily life. And medication, if appropriate, can often significantly impact neurotransmitter regulation and improve emotional control.

The journey of understanding and managing your ADHD-emotion connection is ongoing. It's about empowering yourself with knowledge, fostering self-compassion, and actively building a toolkit of strategies that work with your beautifully chaotic brain, not against it.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: Is emotional dysregulation a separate condition from ADHD?

A1: While not formally listed as a diagnostic criterion for ADHD in the DSM-5, emotional dysregulation is widely recognized by researchers and clinicians as a core and highly prevalent feature of ADHD. It's considered an intrinsic part of how ADHD impacts executive functions and brain physiology, rather than a separate, co-occurring disorder.

Q2: Why do small things trigger such big emotional reactions in my ADHD brain?

A2: This often comes down to an overactive amygdala (your brain's emotional "smoke detector") and an underactive prefrontal cortex (the region for rational modulation). Your brain is quicker to perceive threats or emotional triggers, leading to intense, rapid responses before your thinking brain can regulate them. Reduced executive function, like inhibition, also means you have less "brake" on these initial reactions.

Q3: Does dopamine really cause mood swings in ADHD?

A3: Yes, dopamine plays a significant role. ADHD involves dysregulation in how the brain processes dopamine, which is crucial for motivation, reward, and emotional stability. This can lead to rapid fluctuations in mood, energy, and focus as dopamine levels rise and fall, resulting in intense highs followed by "crashes." Building consistent routines and seeking predictable positive reinforcement can help stabilize dopamine.

Q4: How does Polyvagal Theory help me understand my ADHD emotions?

A4: Polyvagal Theory explains how your nervous system constantly assesses safety and shapes your emotional responses. For ADHD brains, this "neuroception" is often biased towards threat, leading to frequent states of "fight or flight" (anxiety, irritability) or "freeze/collapse" (overwhelm, numbness). Understanding these states helps you recognize when your nervous system is activated and apply techniques (like deep breathing or rhythmic activities) to promote a calmer, more regulated state.

Q5: Can medication help with emotional dysregulation in ADHD?

A5: For many individuals, ADHD medication (stimulants or non-stimulants) can significantly improve emotional regulation. By optimizing neurotransmitter function (especially dopamine and norepinephrine), these medications can enhance executive functions, calm the amygdala, and improve the brain's ability to modulate emotional responses. It's a discussion worth having with your doctor.

Q6: How is ADHD emotional dysregulation different from Bipolar Disorder or BPD?

A6: While there can be surface-level similarities (e.g., mood swings, impulsivity), the underlying patterns differ. ADHD emotional dysregulation is typically reactive (triggered by immediate events) and rapid-cycling within a day, without distinct, prolonged manic or depressive episodes lasting weeks/months (like Bipolar). BPD involves a broader, chronic pattern of unstable self-image, relationships, and identity, which isn’t central to ADHD. Accurate diagnosis by a professional is crucial.

Q7: Where can I find more support for managing emotional dysregulation?

A7: Beyond the insights shared here, consider:

- Therapy: Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) and Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT) are highly effective in teaching emotion regulation skills.

- ADHD Coaching: Coaches specialize in helping you implement practical strategies tailored to your unique ADHD brain.

- Support Groups: Connecting with others who share similar experiences can provide validation and a sense of community.

- Continued Learning: Explore authoritative resources like ADDitude Mag and CHADD for further expert insights.

Ultimately, understanding the "why" behind your emotions is empowering. It transforms what might feel like personal failings into neurobiological realities, allowing you to approach self-management with informed strategies and compassionate self-awareness.